|

The commemoration of Tisha B’Av, the anniversary of catastrophic events in Jewish history (including the destruction of the First and Second Temples) occurred on a Thursday this past year. I have written before about my own ambivalence about the day (well, I am not so ambivalent, but that’s a different story). But in Israel, it remains a big deal. Especially for those who are religiously observant, the weeks leading up to this date are increasingly morose, with certain pleasures discouraged and an emphasis on the seismic shifts that devastated the Jewish people thousands and hundreds and dozens of years ago. The day itself includes fasting, mourning practices, and the recitation of Lamentations, which is not an easy book to read in any circumstance. The Shabbat that follows is called the sabbath of consolation. The prophetic reading begins with the words, “Comfort, comfort, oh my people,” and the section of the Torah recited includes the Ten Commandments and the Sh’ma, arguably the signature affirmations of our relationship with the divine. In synagogues and study halls, rabbis and other teachers teach or preach on those themes. I took notice this year that the messages and sermon prompts sent out by denominational and educational organizations (and individual rabbis) arrived, as usual, mid-week. They mostly noted the week’s focus on grief and desolation, but they all focused on the message of comfort that comes with Shabbat. It is not news that I am retired for about a year now. I no longer spend any time during the week wondering what message I will deliver to my congregation, IRL or virtual. Likewise, I no longer lead a congregation in prayer, so I am released from the responsibility to keep them on the same page (literally) or offer gentle hints about when to stand, sit, sing, or silence. The first year in more than 40 that I attended High Holy Day services as a Jew in the pew (after I left my congregation), I was astonished and deeply moved by the liturgy in a way I had never experienced. It moved through me like a river, inspiring and immersing my only audience: me. All of the preparing and explaining I had done for others had come to rest in my very personal experience of prayer and penitence, and I remember thinking, “Oh, so this is what it is like!” Me. The rabbi. So, almost ten years down the road, it struck me that my friends and colleagues who take Tisha B’Av so seriously must, ironically, refuse themselves the experience of being awash and saturated in the meaning of the season to look ahead to comfort before its time. As we joke with each other all the time, “sermons don’t write themselves;” they require reflection, preparation, craftsmanship. Preparing one takes you from today and transports you to tomorrow or the next day, asking you to prophesy what concern of heart and mind you must address for people who do not yet themselves know the answer. The rabbi – really any clergy of any faith -- is the one person cheated out of the phenomenon of the moment in a roomful of people anticipating that moment. The cost of deepening an experience for others, in a classroom, online, or from the pulpit, is stepping out of the moment before its time and denying yourself the fullness and richness of that experience you so faithfully commend to others. As the agent of spiritual surprise, the surprise is lost on you. As the guide to hidden awe, the awe is revealed absent its context. I think that mostly I didn’t notice it until recently. After all, it’s what I did: pastoring, preaching, promoting, pointing. For as much as I talked about the past and the present, I myself had no choice but to live a significant part of my life in the future. I will say now, after noticing others living my former life, I am glad to be able to leave the future behind.

0 Comments

Among the Americans we all ought to know better is Howard Thurman. Though he died over forty years ago, the insights he shared are timeless. He was a Christian and a Black man, and like other remarkable believers like Thomas Merton, Thich Nhat Han, Abraham Joshua Heschel and Dorothy Day, he managed to translate his deep personal faith in the God posited by his religion and nourished in the community of his identity into teachings that were meaningful to all.

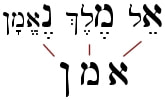

I have the privilege to spend an hour every couple of weeks with people whose names you would recognize as important and responsible public figures. We talk about the rich landscape within that too often goes unexplored in the commotion of their calling to service. And lately we have used, to great effect, some of Thurman’s words. (The question I am asked more than any other about this group is if they are all Jewish. I am not sure why it matters, but the answer is no. But I still am.) Here is the quotation we used recently. It comes from an address he delivered near the end of his life at Spelman College entitled “The Sound of the Genuine.” There is something in you that waits and listens for the sound of the genuine in other people. And if you can’t hear it, then you are reduced by that much. If I were to ask you what is the thing that you desire most in life this afternoon, you would say a lot of things off the top of your head, most of which you wouldn’t believe but you would think that you were saying the things that I thought you ought to think that you should say. But I think that if you were stripped to whatever there is in you that is literal and irreducible, and you tried to answer that question, the answer may be something like this: I want to feel that I am thoroughly and completely understood so that now and then I can take my guard down and look out around me and not feel that I will be destroyed with my defenses down. I want to feel completely vulnerable, completely naked, completely exposed and absolutely secure. I no longer carry the responsibility of writing and delivering sermons, even during the sacred times of the High Holy Day season. When I did, I usually asked myself what the message was that I needed to hear. Too often, especially in my younger years, that message had to do with matters of politics. Somewhat less often, I felt compelled to defend the particularity of Jewish life, likely a reflection of my own insecurities. These days, my message to myself would be different. It would be much more akin to what this grandson of a slave sought to convey to the promising generation of proud and educated younger versions of himself. Were I facing a congregation of Jews during this time of repentance who had committed some part of three full days articulating their contrition and their intention to live a better life, I think I would urge them to be less concerned about ticking off a list of shortcomings and aspirations. I would not do away with them; in fact, the common liturgy recited in the company of others is the best way I can imagine to open the channels of introspection without being swept away by the fear of self-humiliation. But the real goal of these Days of Awe must be what Howard Thurman was brave enough to say: I want to feel that I am thoroughly and completely understood so that now and then I can take my guard down and look out around me and not feel that I will be destroyed with my defenses down. I want to feel completely vulnerable, completely naked, completely exposed and absolutely secure. The assurance that any good faith tradition brings (and, I am sorry, but if your faith tradition doesn’t bring it then it is not so good) is that if you will have the courage to be completely exposed you will nonetheless be absolutely secure. You will be loved, not in the sense of admired or adored, but in the sense of affirmed for who you really are. And if you do not profess a faith in some locus of wisdom or power outside yourself, then what you must expect from your most cherished relationships is no different. It places a burden on the people in your life as they struggle with their own courage, but that’s the price of love. If you will be in synagogue, actually or virtually, in these weeks ahead, I wish success for you in this endeavor. If not, I wish success for you wherever you find it. As I said, I no longer carry the responsibility of writing and delivering sermons. But if I did… Interfaith Alliance has been a touchstone in my life for more than twenty-five years. I remember when I was “recruited” to join the board as part of the cohort of clergy of the rising generation of leaders. The opportunity to sit at the table with people I admired from afar – Herb Valentine, Joan Brown Campbell, Denny Davidoff, Albert Pennybacker, Arthur Hertzberg – was too delicious to pass up. The cause was incidental. At first. In those first years, our finances were tenuous. An opportunity presented itself for a windfall – a very popular recording artist was willing to do a benefit concert at no cost to us. It had the potential to pull us out of a deep hole. The only night the artist was available was a Friday. Without hesitation or prompting, the chair, Herb Valentine, said, “We can’t exclude our Jewish brothers and sisters by holding this concert on Shabbat.” There was no disagreement. I learned in one sentence the importance of standing with partners and allies, even to the point of personal and institutional disadvantage. Underpinning the personal integrity of this extraordinary group was, I learned quickly, a profound commitment to the First Amendment’s insistence on freedom of conscience. The principles that Interfaith Alliance upholds as an organization are a reflection of the constitutional guarantees that inspired it. The early iteration of what is now the Religious Right – the Moral Majority, the Christian Coalition, and others – pioneered the notion that our first freedom existed to protect the privilege of certain adherents of their own tradition. The benefits to others were crumbs from the whole loaf of privilege they claimed. But Interfaith Alliance insisted on the proposition that all conscience is created equal, including that which is not Christian and even that which is not religious in nature. I will admit that I was initially challenged by the notion of defending people whose beliefs and practices were profoundly different from my Judaism. But Rev. Valentine’s example inspired me. And when we had the good fortune to engage Rev. Dr. C. Welton Gaddy as our president, I was able to learn from the master as I continued as a board member, officer and chair of the board. Welton’s willingness as a Baptist preacher to embrace the equality of all people, regardless of faith, identity, or politics remains my model. When it came time for Welton to retire, the board (on which I no longer served) had an understandably difficult time finding a successor. He called me and asked if I would fill in for him for a few months as the search process played out. That temporary assignment turned into more than seven years of protecting faith and freedom, as our mission insists. Slowly but steadily over these many years, the people of Interfaith Alliance have come to understand that religious freedom is about more than keeping prayer out of public schools and supporting the right of an individual to wear a yarmulke, hijab, or turban. So much of the institutionalized bias in our country has its roots in religiously-motivated prejudice. That includes the mostly-Protestant custom of public prayer, presumed to be a norm because of long-standing practice. But it also includes diverting public school funds to religious education, delegitimizing homosexuality, and denying reproductive health care and medical procedures. Freedom of religion is a guaranteed starting point for every citizen. It is not, as some would have, toleration for dissent from a public standard that is really someone else’s private belief. The landscape has turned pretty ugly during my tenure. I admit to being lulled into a sense of optimism when the Supreme Court affirmed marriage equality, but not long afterward the surge in blatant bigotry that coincided with the change in administration persuaded me that the most important work of Interfaith Alliance is still ahead. There is no more fundamental human right than freedom of conscience. The only limitation on belief should come from the protection of similar freedom for others. The adage attributed to Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, “the right to swing my fist ends where the other man's nose begins,” is, of course, a metaphor for all human rights, but none more so than the inviolability of personal conviction, until and unless it interferes with the same right of others. If I do not protect that right for you, then my right is at risk. I have been blessed with a passionate staff and committed board grappling with the dilemma of all people who understand that no aspect of our freedom is independent of any other. The common (and to some, controversial) term for this is “intersectionality.” But to claim that religious bias is at the root of all of our ills is to stand for everything and nothing simultaneously. (I will admit to saying that nothing prevents religious freedom more effectively than a bullet). Instead, I have learned that our partnerships and coalitions enable us to do what we do uniquely and best: serve as watchdogs and advocates in the struggle to preserve the integrity of the first freedoms in the Bill of Rights – the separation of religion and government and the preservation of the essential right to conscience. That is why I will continue to support the unique mission of Interfaith Alliance and its equally unique locus in the cohort of civil liberty organizations. We continue to support the Constitution as a consequence of faith, and faith as a consequence of the Constitution. I hope you will continue to join me. In gratitude, Rabbi Jack Moline President Emeritus I hear that it is the conceit of every generation that its times are unique and demand innovative responses to familiar situations. Usually, as the French say, the more things change, the more they stay the same. However, in at least one circumstance, our generation has reached a fulcrum point that cannot be ignored. Created by the quarantine demands of the coronavirus, synagogues have had to innovate the way in which worship is conducted. Since gatherings in close quarters to speak and sing posed a danger to health and even life, any community not in denial has had to choose between discontinuing in-person communal worship or including a virtual platform for participation. Most chose the latter, though not all in the same way. Some limited online worship to weekdays out of respect for shabbat restrictions. Some abridged the service to omit the sections that require the presence of a minyan (quorum) in person, usually with the exception of the Mourner’s Kaddish, recited by the bereaved and those recalling the anniversary of a close relative’s death. Some allowed for a hybrid platform, inviting a minimal number of people to the synagogue, and including others through an online link. Some opted for the interactive online approach, e.g., Zoom, and others for livestreaming, the internet equivalent of a broadcast on television. This much is certain: after more than two years, alternative ways of attending worship have become integrated into the lives of those who conduct worship and those who participate. This is not the first time that technology has redefined collective prayer, including the complicating factor of an unexpected catastrophe that made change necessary. For example, Ezra, the Biblical scribe, committed the heretofore oral transmission of the Torah to parchment and instituted public readings to take advantage of the twice-weekly crowds in the marketplace. At least part of his motivation was the influx of foreign spouses in the Jewish community whose unfamiliarity with the requirements of Jewish practice was, in his perception, reducing the commitment of the Jewish family members. The custom of reading from the Torah on Mondays and Thursdays survived the reliance on the commercial marketplace and took its place in the synagogue, especially after the locus of collective ritual practice shifted from the destroyed Temple (and early local sacrificial altars) to buildings dedicated to gatherings for ritual prayer and learning. Initial practice in the Holy Land was individualized by community; it took more or less than three years for any locality to complete the reading of the Torah, depending on the expositions prepared by local scholars. Eventually, the reading of the Torah was formalized and codified into a yearly cycle, especially as the dispersion of the Jews throughout the world created a need to keep everyone literally on the same page for the sake of unity. The development of vocalization and cantillation marks, what we today might call vowels and musical notations, influenced by other surrounding cultures, also innovated the study and presentation of the sacred texts, not only of the Torah, but of the entire Bible (including the narratives about Ezra the scribe). Once the regimen of prayer became more usual, technology and circumstance also provoked change and some measure of standardization. The central, perhaps original, section of the various daily worship services became known as the “18” (in Hebrew, “Sh’moneh Esrei”) for the number of standardized blessings that were recited, beginning close to 2000 years ago. Famously, one rabbi taught that if one could not recite the full 18 as standardized, it was better to recite “something like (the) 18,” that is, an approximation in either number or content. The popularity of gathering for worship demanded the construction of larger and more sophisticated synagogue buildings, and the development of experts in conducting the standardized services. Today we call those professionals cantors and rabbis; then they were called only “emissaries of the community” (a term still used to describe the leaders of worship generically). The synagogue in Alexandria, Egypt was so large and so well-attended that people farther to the back could not hear the leader clearly, so technology was deployed: flags were waved to signal the liturgical responses even if the worshippers were not technically participating in the reading of the prayers. Everything changed with the invention and popular spread of the printing press. Now, the entirety of the liturgy could be put in the hands of the individual. There was no need to rely on an expert or savant who had memorized the prayers. The technology drove the atomization of the community – people could gather for communal worship in groups as small as 10, and individuals unable to attend such a gathering could be certain they followed to the letter what was once a bit more free-form. In fact, the improvisation of prayer was virtually eliminated once it was codified in print. And speaking of the minyan, it is worth noting that even in that formative period of public worship, there was a debate over the use of technology. Finding a quorum of ten sometimes presented a challenge. What constituted a worshiper, the rabbis asked? Could a “golem,” a legendary creature sculpted of mud and animated by an incantation, be counted to round out a group of nine men? (No, they answered.) To this point, it is worth noting that in retrospect, all the debates over changes were resolved. Some were resolved by debate, others by fiat and still others by practical circumstances. However, until they were resolved definitively after some greater or lesser period of time, practice was fluid, with some communities relying on different modes of presenting Torah, some reciting different versions of the prayers, some allowing different ways of including ten for minyan. (No one included a golem, by the way. However, some included people unable to hear and/or respond to the prayers.) These few examples from many others illustrate the challenge facing us today as we try to maintain one of the central markers of a sustainable Jewish community: collective worship. Whether the service is conducted three times each day, as in those communities that consider themselves traditional, or only on Shabbat, as in those communities that do not organize daily worship – or any configuration in between – to the point of the emergence of covid-19, the only standard for communal worship was gathering in person. Even those few communities that cultivated an online presence continued to hold a ”live” service whenever the virtual presence was included. During this past year I was bereaved and undertook to recite Mourner’s Kaddish three times a day for eleven months. What would have been a frantic dash around town in more normative times became a simple click of a mouse early morning and late afternoon (for afternoon and evening prayers). The online communities I visited, each with its own rules for determining a minyan, were mostly well-attended every day. Even synagogues that struggled to gather ten in person found a regular attendance in multiples of ten on any given weekday morning or afternoon. The one I attend most regularly can count on twenty-five to thirty worshipers on the slowest day. A Saturday night service from another congregation regularly attracts upwards of sixty, despite the irregularity of the time the sun sets from week to week. The worship itself took some getting-used-to for a person like me, familiar with being among others in person. But the community that formed around that service was warm and personal, almost never including the impatience of someone who was called to help “make the minyan” or whose bus to work was leaving precariously close to the end of a service even slightly delayed. Indeed, the conversations taking place among these online worshipers now surrounds the question of whether and when to return to in-person worship and what to do about those who have come to rely on the spiritual nourishment and social interaction of virtual gatherings. Overwhelmingly – even among those who will return to in-person worship – there is an insistence about the importance of an on-line option. What will the rules turn out to be? Part of the answer depends on the nature of the question. Is the goal of daily worship to maintain the format for worship or to widen the population that participates? That is to say, is it better to struggle daily to gather ten people in person or to encourage twenty-five to continue to join virtually? I believe the lesson of our history is to seek a balance between precedent and innovation. The goal of a learning and striving Jewish community should not be merely bragging rights that a dozen devoted individuals maintain the minimum of ten for daily worship. Rather, the opportunity for dozens more to engage regularly and to encourage friends and fellow Jews to participate should drive our willingness to take advantage of this change in circumstance forced upon us and be the impetus for a new and additional way for people to be full participants in the practice of daily prayer.  Praying with a minyan is preferable to praying alone. People who are accustomed to that regular practice – especially the same community regulars – develop the habits of local custom. These include when to stand or sit, what melody to use, where some psalms are inserted and more. Those customs can become muscle memory. Just before the recitation of the Sh’ma morning and afternoon, the siddur includes the instruction that a lone worshipper should quietly recite three little words, eil melekh ne’eman. The acronym for that brief acknowledgment of God’s faithful sovereignty is the very familiar “amen.” I suspect, without any scholarly proof, that the custom of responding “amen” to a blessing recited by the leader is almost an autonomic reflex. And because one should not respond with that affirmation of “amen” to one’s own blessing, this little euphemism sort of protects the individual from inadvertent error. I don’t want to argue my explanation, just my point. People become accustomed to not just the rituals of prayer, but to its habits as well. And the understanding is well-articulated and demonstrated in the tradition that the strength of custom is frequently superior to the requirements of the law. Custom must be considered in all matters of observance. And sometimes, people affirm a custom that defies a certain logic. Take for example the practice of covering one’s eyes when reciting the Sh’ma. I never saw it as a kid, some sixty years ago. When it gained popularity as time went on, it was explained as a means of blocking out distractions and focusing on its singular (no pun intended) message when the statutory recitation during the body of morning and evening prayers took place. Today, I see most members of some congregations cover their eyes during the opening introductory prayers, the Torah service and the amidah of musaf when the six words are recited. (As you might be able to deduce, it is not my custom.) A moment of voluntary blindness has become an essential part of the declaration. In the time when the new month was declared only by the testimony of witnesses, there were people who took that witnessing very seriously. I make no representation about their general piety, but if they witnessed the new moon on Shabbat, they set out immediately to be available at the moment the court reconvened to testify. The Mishnah (RH 1:6) recounts what my teacher, Rabbi Rachel Ain, calls the value of the volunteer. (This is the expanded translation from Sefaria.) There was once an incident where more than forty pairs of witnesses were passing through on their way to Jerusalem to testify about the new moon, and Rabbi Akiva detained them in Lod, telling them that there was no need for them to desecrate Shabbat for this purpose. Rabban Gamliel sent a message to him: If you detain the many people who wish to testify about the new moon, you will cause them to stumble in the future. They will say: Why should we go, seeing that our testimony is unnecessary? At some point they will be needed, and no witnesses will come to the court. Someone else can discuss the hierarchy of the mitzvot. Is Shabbat more important (R. Akiva), is the willing spirit more important (R. Gamliel) or is the witnessing more important (the Mishnah itself)? For my purposes, the critical takeaway in my theoretical agreement with Rabbi Akiva is that the legitimacy of the witnessing is not compromised by the violation of standards of Shabbat observance. For my purposes, the critical takeaway in my practical agreement with Rabban Gamliel is that people should not be discouraged in their desire to do the right thing. I was bereaved this past April. My mother went to her eternal reward very early on the second day of Pesach and I, like so many others during this pandemic, had to find the way to mourn her without the ability to be enfolded in visitors during week of mourning and among an in-person minyan during these eleven months of daily kaddish. The erudite emergency instructions that emerged from the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards were equivocal about the nature of a virtual minyan. Some of the synagogues I attended conducted worship on Zoom as if everyone was together in a room. Some modified certain parts of the service – especially reading the Torah. And some conducted the services as if it there were no minyan, eliminating the prayers that require a quorum…except for mourners’ kaddish. Had you asked me before the pandemic, or even in its early days of quarantine about the “validity” of a virtual minyan, I would have been skeptical at best. But in the best example of the remarkable adaptability of the human community, I have discovered the warmth and support of all sorts of folks in all sorts of places who remain committed to daily worship for its own sake. Certainly, as in “regular times,” there are those who come to fulfill their obligation to kaddish. But the thirty or more people who log on to my regular morning and afternoon-evening prayers each day are overwhelmingly there for the prayer – and each other. A new normal has been established. Will it survive the restrictions demanded by preserving life and health? Part of me hopes so, though I long to spend some time schmoozing with my new community over a cup of coffee and a Danish. But of this much I am absolutely certain: anyone who recites those three little words before reciting the Sh’ma on a Zoom minyan does not recognize the wisdom of Rabban Gamliel.  On the corner of two local through-streets sits my favorite church. Westminster Presbyterian is a local landmark. It towers over the elementary school to its right and the firehouse to its left. You can’t miss it. In fact, if you fly into Reagan National Airport and the approach is from the south, its steeple is clearly visible as you land, sticking up from the canopy of trees. The church helps to fund the annual budget by housing a cell tower up there for at least two major carriers. Westminster is my favorite for a lot of reasons, including the dear friend of mine who leads it. It is home to a remarkable group of members who were the vast majority of the last social experience I had before the pandemic forced us all into isolation. They helped Pastor Larry Hayward, Pastor Maggie Hayward (yes, they are married; no, they are not co-pastors) and me fill two whole buses to tour Israel at the end of February. It was our third interfaith trip. The population of the church, like most religious communities in the DC area, includes lots of people doing the ordinary things that ordinary people do, and a smattering of people whose professions influence the course of the nation. They are Democrats, Republicans, fierce independents, natural-born citizens, immigrants, wealthy and just-getting-by. And, to a person, welcoming. I used to have an almost-infallible memory for names. But as I have gotten older and the sheer number of people I meet has ballooned, I am not quite so confident. So to avoid embarrassing myself, I now almost always greet people I sort-of know by saying “Hi, I’m Jack Moline.” By putting it out there that they might not remember me, my hope is that they will reply with their own names. The ritual continues with one or both of us responding, “of course I know you.” Mostly, it is true. When it is not, it at least provides some context for the encounter. I have been introduced to one political figure many times, and he never remembers who I am. That’s just fine, because he meets a gazillion people a year. But my name and my yarmulke always trigger his memory, and the conversation always turns to whatever Bible passage he has been reading that week. It is refreshingly different from the “nice-to-meetcha” mantra that is otherwise inevitable. The other result of my name game is to remind myself that I should not presume that other people know who I am. It is a lesson in humility that is worth learning and relearning when you live a semi-public life and can be seduced by the notion that you are kind of a big deal. (I was once at a social function, standing next to my wife, when a guy I did not recognize came up and tried to hit on her. When he asked her name, he recognized “Moline” and said, “Are you related to Rabbi Jack Moline?” “He is my husband,” she answered. “How is Jack doing?” he asked. “Why don’t you ask him yourself,” she said, “He is standing right next to me.”) As I said, Westminster is a local landmark. Its big front doors open to the intersection on Sunday mornings. The courtyard next to the sanctuary is a surprisingly effective refuge from the traffic on the street. The parking lot across from the fire station takes up half a block and backs up to the park behind the school. The large marquee sign planted toward both cross (!) streets usually advertises the topic of the sermon ahead, along with which clergy person will be preaching. (Lately, it offers options for on-line and limited in-person attendance). You can’t miss it. If you park in the lot and enter the door that leads to the church offices, the chapel, the meeting rooms and classrooms and the best place to hang your coat on the way to the sanctuary, you absolutely know where you are going. You would not think you were entering George Mason Elementary School or Fire Station #3. But posted right next to the door is a modest sign on which are painted the letters spelling “Westminster Presbyterian Church.” Just in case you don’t remember. Just in case you don’t know. Just so you know you are in the right place. Just so you know you are welcome. It is a lesson in humility worth learning and relearning.  I have a friend who holds elective office who called me last week to ask me an ethical question. They were offered the opportunity to jump ahead of the line and receive the covid vaccine months before they would be otherwise eligible. It was tempting. People in their family were immuno-compromised and the conduct of the office would be much easier without the constant fear of exposure to staff, constituents and others whose level of contagion was indeterminable. They asked me as a rabbi – is it ethical? Before I tell you what I said, let me own up to envy. I am 68 years old and I have two medical conditions that put me in the third tier of eligibility. Once the health care workers and nursing home residents are inoculated, I will be next. But since Thanksgiving, thanks to the expected (and realized) surge of cases, I have diligently followed CDC recommendations and kept away from just about everyone. I haven’t gone to the grocery store, gotten a haircut, picked up my prescriptions, personally patronized the local businesses I have tried to support. Someone else (usually my younger and healthier wife) has done all of those things for me, except for the haircut (which you would know immediately if you saw me, which you won’t). Each day, I get my exercise in by walking for close to an hour on a route that gives me plenty of room to stay multiples of six feet away from any other human being. If I see someone I recognize, I wave and shout. I have not held my grandchildren, who live just an hour away, in just about four months. I know that still makes me luckier than a lot of people, but four months in the life of a toddler is a forever of new experiences. My routine is routine. It includes reading the newspaper each morning and, not unusually for someone my age, watching both local and national news on television each evening. Even if you get your news from Facebook or Twitter, you know what I encounter every day. The pandemic stories do not vary, but they still break my heart. Nurses in tears because they have never lost so many patients. Families devastated for the crime of a birthday party. A wizened doctor pleading with people to wear a mask so they won’t die. Grandmothers sitting in mile-long lines of cars hoping for a test or a bag of food. Single moms worried that they will be evicted because the rent is six months overdue and public assistance has evaporated. But aside from the horrifying loss of life, the worst story for me was about the clinic that somehow got hold of a few hundred doses of vaccine and made them available to members of the owners’ faith community. Black market Moderna, as if they were starving Jews living in the ghetto. Jews they were, as a matter of fact. They were willing to take those doses away from the doctors who were treating strangers in ambulances, from frail elderly imprisoned in nursing homes, from EMTs and firefighters and police who were tending to the victims of belligerent bar-hopping with naked faces. They reached out to certain respected rabbis from their community, men who were rightly embarrassed to discover that they were receiving contraband. But they did not reach out to Catholic priests, to Imams, to hospital chaplains caring for their own broken-hearted communities. The Talmud discusses the dilemma of two men stranded in the desert, one with just enough water to survive and the other with none. What should they do? If one drinks, the other dies. If both drink, both certainly die. The conclusion, taught by the pre-eminent rabbi of all time, Akiva, is that the person with the water must drink and survive. Tragic though it may seem, he may not forfeit his life for another, and he may not forfeit both lives for the sake of principle. His claim on life in a time of scarce resources is non-transferable. Those diverted doses of vaccine were spoken-for. The clinic owners stole life from a beloved uncle, an overworked respiratory therapist, the kid who delivers their groceries. I really, really miss my grandchildren. I told my friend that, ethically, they could not jump the line. There is a blessing in my tradition that acknowledges a unique transition for parent and child. When that child comes of age – the tradition has settled on age 12 or 13 – parents recite words of praise and acknowledgment of God “who has released me from the punishment of this one.”

The belief system of most modern Jews gets in the way of understanding the meaning of that blessing. Children are not a punishment, and in our times, parenting is not over as puberty begins. Rather, a child is not considered to have moral agency until adulthood. They may understand right and wrong, but they are considered exempt from liability for their actions until they reach the age at which they can be presumed to have the judgment to be responsible for their actions. But the moral order of the universe demands that no bad deed go unpunished. So, during those years that a parent is responsible for the moral formation of the child, Jewish tradition posits that the misdeeds of the child will be visited on the parents. When the child crosses the threshold to being a grown-up, the parent is relieved (both theologically and emotionally) and no longer held accountable for the consequences of the son’s or daughter’s behaviors. It's not the child who is the punishment, nor the raising of the child. The parent is grateful not to be held responsible for another’s behavior. The concept is akin to putting a ship into port; the captain, relieved to no longer be responsible for the vessel and the lives on board, expresses gratitude, no matter how satisfying the voyage. I am writing this column on July 1, 2020. In an alternate version of my life, today would have been the first day after the last day of my career as a synagogue rabbi. The agreement I had with my long-time congregation was set to expire yesterday, the end of an arrangement we entered when I was still responsible for all three of our children, who are now in their thirties. The details are unimportant except that the congregation and I wisely built in moments of reconsideration, and six years ago I exercised that option. In my opinion, I could no longer provide the care and attention my congregants deserved. I am asked all the time if I miss it, and the answer is an unmitigated “no.” I think I did pretty well during close to thirty-five years, and I held myself to a standard of integrity I was no longer able to uphold to my satisfaction. Relieved of the expectations that come with leading a community, I have had the freedom to reconsider my own beliefs and practices. They are clarified in a way that put me at odds with some of the most important responsibilities of a community’s rabbi. I was right to retire. I am asked rarely if it has been easy, but if I were, the answer also would be “no.” Maybe I had a romantic notion of what it would be like to be a “Jew in the pew,” but it was an unrequited romance. I did nothing to prepare my congregation to deal with a local emeritus. They did less. Without that guidance, my sense was that I was like (you should pardon the expression) the ghost of Christmas past – undeniable, but not especially welcome. My hopes of finding a place to contribute to and benefit from my community did not come to fruition; in fact, they were regularly frustrated. For a long time, I was resentful. A different set of emotions has taken hold during these peculiar months of quarantine. Understanding that no amount of objection in my heart would change the decisions about my role that have become the default settings in the synagogue was an important first step. I could argue their wisdom or foolishness, but the debate would never be settled. No one aside from me was even interested – at this point, both understandable and practical. But I ask myself what my life would be like during this pandemic if I had the responsibility in the last fifteen weeks of my tenure to reimagine entirely the way to care for a congregation I had pastored for more than thirty years. If my energy and integrity to lead the synagogue was insufficient in more normative times, toughing things out in quiet distress could have only undermined the necessary changes in this time of challenge. Knowing myself as I do, I would have suffered from a deep sense of inadequacy and taken on myself any decline in its vitality and ethos of community. Never mind, by the way, that my inclination to hold myself liable for shortcomings (yet not commendable for successes) was likely a major contributor to my exhaustion before my time. The serendipity of my earlier choice has brought some clarity to at least some part of this specific day. I would have borne the responsibility and, in some measure, punished myself, as most rabbis do, for the sins of omission and commission during these weird and unfamiliar times. To exploit the metaphor of the ship, I am grateful that a new captain took over in the last port, because I am not sure I would have put into this port successfully. So, it seems right and proper to recite the aforementioned blessing on this day. I can’t remember if I said it six years ago; if I did, it was in a very different state of mind. Today, I understand it as I believe it was intended: a recognition that, having met my obligations to others, it is now incumbent upon them to meet their obligations to themselves.  My first sabbatical from my work as a rabbi came eleven years after I arrived at my pulpit. I was exhausted, and I spent much of the first half of my six months trying to regain some equilibrium. I began to refer to it as “emotional rehab.” In the course of reflecting on the process, I realized that the demands on my emotions had overwhelmed them. I was expected to take care of my congregants, to acknowledge their experiences and to support them in their passages through the reactions they felt. I was allowed to be sad at a death, but not to be dissolved by grief. I could rejoice at a birth, but not be carried away by it. I was expected to be supportive of the bar or bat mitzvah student, but only very carefully critical. As a result, I became adept at tamping down my emotional reactions; it soon became (to mix the metaphor) muscle memory. Eventually, I was fried. My emotions had been cauterized. What kind of a life is one without feelings? I was starved to experience the range of emotions as I once had. They had to be intense to get past the scars and scabs that had formed. And what emotion has that power? Anger, of course. I became an anger junkie. I looked constantly for opportunities to feel outraged, insulted, unpleasantly shocked or infuriated. It was no way for a rabbi to be. I recovered pretty well after six months, and I was able to recognize the signs of relapse. I’d like to think I also became more aware of the cauterization of emotions that others were experiencing. Not everyone reacted the same way to the need to resist being swept away and, therefore, suppressing feelings. But when enough people do so it can have a spill-over effect on society as a whole. That’s why I believe we are living in an age of cauterization. There is no doubt that we are experiencing change in almost every corner of our lives. The result has nothing to do with the desirability of that change, rather the fact of it. Nothing is reliably the same any more. Technology enhances and intrudes on our daily existence. Sexuality, sexual identity, sexual orientation and same-sex relationships have become variegated notions, a challenge for people who feel uncomfortable with the very word “sex.” Weapons are presumed to be everywhere – the theater, the airport, the school, the church, the neighborhood. Fewer and fewer people affirm what was assumed to be universal – God – and those who continue to believe dismiss beliefs at variance with their own. Even television, which a generation ago called families to the same room at the same time (quality aside), now has splintered those who stream their preferences on multiple screens and devices. How does a person respond? It is simply not possible to cope with the constant anxieties and confusion that result from constant change. Merely maintaining an equilibrium takes emotional energy that cannot be spent elsewhere. Public figures have famously railed about “political correctness” (which is itself an expired idiom), but they offer no reassurance to those whose nerves are frayed and who fear that they will be without capacity to gain a footing in a shifting landscape. We are afraid of love. We are afraid of what we hear. And we are afraid to laugh. It seems to many that there is someone waiting to level an accusation of inappropriate, even criminal behavior. Making ourselves vulnerable provides an opening for what we suspect will be a frontal attack. We rehearse new words, new phrases, even new pronouns and cauterize our genuine feelings that need time and space to adjust to the changes that inundate us. What is left to feel? What emotion has the intensity to get past the scabs and the scars? Anger, of course. We have become anger junkies, gathering by the thousands to cheer insults against others, mouthing personal attacks against former friends and allies, belittling the people who disagree with us rather than engaging the disagreement. Every challenge is deemed bullying. Every cruelty is deemed justified. Every motive is deemed nefarious. It is no way for a rabbi to be. And it is no way for anyone else to be. And it is especially no way for a nation to be. Dr. King famously lifted up the beloved community. The phrase has specific meaning, but never mind what it is. Go with the very idea. Every member beloved. The chorus of voices and ideas both harmonious and dissonant. Every encounter, an opportunity to delight. That’s what we need. There are practices we can all develop that are curative – not just palliative, but curative. If you are deliberate about pursuing three things, you will be happier and therefore less angry. The first is love. And by love, I also mean sex. Physical intimacy is just as important as platonic friendship, though there is nothing wrong with that either. The touch of another person, tender and sincere, is probably the most effective way to recover a sense of openness to the world. Physical intimacy is not necessarily the same as intercourse or any of the variations of what is euphemistically called penetration. A kiss, a back rub, a caress or an embrace gives each person the reassurance that they are desired and desirable. It is a gift that may be unexpected but is always hoped for. Of course, love must always be invited, never coerced. And by that, I also mean sex. How ironic that the very same acts that can bring comfort and satisfaction when desired can further fray the nerve endings when imposed. The second is listening. And by listening, I especially mean listening to music. Yes, you should show an interest in what other people have to say. But if you are hoping to rehabilitate your capacity to feel, there is no more effective place to lose your dullness than in the tension and release that is the essence of musical expression. I have my own preferences, and I suspect you have yours. But you should be open to opportunities you might not initially elect. I am always lifted by “The Blue Danube Waltz.” Lennon and McCartney’s “I Will” is my own favorite Beatle’s tune, and my kids are still embarrassed by my air guitar to their “Birthday.” But nothing opened my heart and my tear ducts like the performance by Yo-Yo Ma’s Goat Rodeo ensemble of an old Irish folksong, “All Through the Night.” Not every kind of listening works for me. And by listening, I also mean music. Taste is a peculiar thing, very personal. Music can reinforce your need for anger, not only calm it down. Lyrics and volume that give expression to frustration or belligerence can serve as a release of tension or as reinforcement. More irony – not every song soothes. The third is laughing. And by laughing, I also mean doing so inappropriately (occasionally). We seem to be in a period of time that disparages humor. I can’t imagine a world without laughter; laughter requires funny; funny always comes at the expense of something or someone (even if it is yourself). Laughter is a release, figuratively and literally. Like music, it involves tension and release. Most attempts to explain humor are dreary (and definitely unfunny). My personal favorite is “the sudden realization of the unexpected.” (I know – too Freudian.) The biggest laugh I ever got was in a college class in which my study group presented on “What Makes People Laugh.” We were mildly well received as we presented examples of various theories. I was assigned the conclusion, during which my friend Bob stood silently next to me. As I spoke, I slowly filled a pie pan with shaving cream. The laughter built with anticipation, but when I ended with Bob still silent and my pie pan full, there was a momentary sense of disappointment. Until I smacked him in the face with the pie. He was “injured,” even as a willing participant. He was exploited. Everyone laughed. Laughing is not always a good thing. And by laughing, I also mean doing so inappropriately. I can’t measure where laughter leaves off and offense begins – it is a moving target. Funny-hilarious to some is funny-cruel to others. If the purpose of funny is to cause harm, the laughter is not palliative, it is anesthetizing, which seems to me to work against the benefit. But I encourage everyone to understanding the difference between stereotyping – not a funny word – and exploiting foibles – a very funny phrase. Yet another irony: if derision makes you happy, you are not really happy. Love, listen, laugh. They are cures for emotional dullness and for the craving for feelings that makes us seek out anger. As individuals, we need all three. As a beloved community, we need all three. The scars and scabs on our collective receptors for joy and grief, awe and compassion, kindness and resolve can be softened and healed. And so can we. More than five years ago I decided it was time to retire from being a pulpit rabbi. I was very tired all the time. It was harder and harder for me to give the members of the synagogue the care they deserved. And I no longer had the patience to deal gently with leaders who felt they could define the responsibilities that I had fulfilled as a rabbi, mostly admirably, for more than thirty years.

|

AuthorI spent 35 years in the pulpit and learned a few things about the people and the profession Archives

July 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed