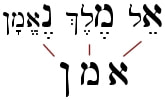

Praying with a minyan is preferable to praying alone. People who are accustomed to that regular practice – especially the same community regulars – develop the habits of local custom. These include when to stand or sit, what melody to use, where some psalms are inserted and more. Those customs can become muscle memory. Just before the recitation of the Sh’ma morning and afternoon, the siddur includes the instruction that a lone worshipper should quietly recite three little words, eil melekh ne’eman. The acronym for that brief acknowledgment of God’s faithful sovereignty is the very familiar “amen.” I suspect, without any scholarly proof, that the custom of responding “amen” to a blessing recited by the leader is almost an autonomic reflex. And because one should not respond with that affirmation of “amen” to one’s own blessing, this little euphemism sort of protects the individual from inadvertent error. I don’t want to argue my explanation, just my point. People become accustomed to not just the rituals of prayer, but to its habits as well. And the understanding is well-articulated and demonstrated in the tradition that the strength of custom is frequently superior to the requirements of the law. Custom must be considered in all matters of observance. And sometimes, people affirm a custom that defies a certain logic. Take for example the practice of covering one’s eyes when reciting the Sh’ma. I never saw it as a kid, some sixty years ago. When it gained popularity as time went on, it was explained as a means of blocking out distractions and focusing on its singular (no pun intended) message when the statutory recitation during the body of morning and evening prayers took place. Today, I see most members of some congregations cover their eyes during the opening introductory prayers, the Torah service and the amidah of musaf when the six words are recited. (As you might be able to deduce, it is not my custom.) A moment of voluntary blindness has become an essential part of the declaration. In the time when the new month was declared only by the testimony of witnesses, there were people who took that witnessing very seriously. I make no representation about their general piety, but if they witnessed the new moon on Shabbat, they set out immediately to be available at the moment the court reconvened to testify. The Mishnah (RH 1:6) recounts what my teacher, Rabbi Rachel Ain, calls the value of the volunteer. (This is the expanded translation from Sefaria.) There was once an incident where more than forty pairs of witnesses were passing through on their way to Jerusalem to testify about the new moon, and Rabbi Akiva detained them in Lod, telling them that there was no need for them to desecrate Shabbat for this purpose. Rabban Gamliel sent a message to him: If you detain the many people who wish to testify about the new moon, you will cause them to stumble in the future. They will say: Why should we go, seeing that our testimony is unnecessary? At some point they will be needed, and no witnesses will come to the court. Someone else can discuss the hierarchy of the mitzvot. Is Shabbat more important (R. Akiva), is the willing spirit more important (R. Gamliel) or is the witnessing more important (the Mishnah itself)? For my purposes, the critical takeaway in my theoretical agreement with Rabbi Akiva is that the legitimacy of the witnessing is not compromised by the violation of standards of Shabbat observance. For my purposes, the critical takeaway in my practical agreement with Rabban Gamliel is that people should not be discouraged in their desire to do the right thing. I was bereaved this past April. My mother went to her eternal reward very early on the second day of Pesach and I, like so many others during this pandemic, had to find the way to mourn her without the ability to be enfolded in visitors during week of mourning and among an in-person minyan during these eleven months of daily kaddish. The erudite emergency instructions that emerged from the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards were equivocal about the nature of a virtual minyan. Some of the synagogues I attended conducted worship on Zoom as if everyone was together in a room. Some modified certain parts of the service – especially reading the Torah. And some conducted the services as if it there were no minyan, eliminating the prayers that require a quorum…except for mourners’ kaddish. Had you asked me before the pandemic, or even in its early days of quarantine about the “validity” of a virtual minyan, I would have been skeptical at best. But in the best example of the remarkable adaptability of the human community, I have discovered the warmth and support of all sorts of folks in all sorts of places who remain committed to daily worship for its own sake. Certainly, as in “regular times,” there are those who come to fulfill their obligation to kaddish. But the thirty or more people who log on to my regular morning and afternoon-evening prayers each day are overwhelmingly there for the prayer – and each other. A new normal has been established. Will it survive the restrictions demanded by preserving life and health? Part of me hopes so, though I long to spend some time schmoozing with my new community over a cup of coffee and a Danish. But of this much I am absolutely certain: anyone who recites those three little words before reciting the Sh’ma on a Zoom minyan does not recognize the wisdom of Rabban Gamliel.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI spent 35 years in the pulpit and learned a few things about the people and the profession Archives

July 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed