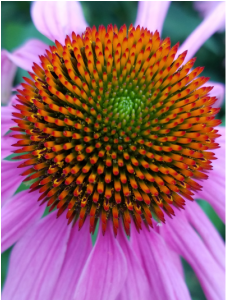

We have an oak tree in front of our house that lends character and shade to our home. Shortly after we moved in, almost 25 years ago, we were told by a wandering tree guy that there was a disease afflicting oak trees that, as yet, had no cure, and eventually the tree would have to come down. Each year, the tree bloomed later and the leaves fell earlier, and now the amount of dead wood in the upper branches means the time has come to take it down. It has gone from grizzled to dangerous. I am sad about the tree. It is not the first one we lost – the one in the back yard that held up our kids’ tree house is long gone. The ones in the city’s right of way with the soft pink blossoms were born to rot, and only a few remain in our neighborhood. But this tree holds great memories, perhaps my favorite being the catnaps I would take on Shabbat afternoons in the fall, leaning against its trunk. Once, my neighbor the yoga instructor asked me what I learned from sitting against the tree and was very pleased that I answered, “The value of being still.” The acorns from the tree became fewer and smaller as the years went on, but I always believed there would be another season because I once learned that a tree puts out its best fruit in the last season before it dies. It “knows” it doesn’t need to hold anything back to recover from the winter ahead. We’re not going to get that last harvest. I walk most mornings in service to my health and to the tracker I wear on my wrist. This morning, thinking about our tree, I happened upon a coneflower plant. (If your browser allows it, there is a picture below.) The coneflower looks sort of like a daisy (they are cousins), but is typified by a spectacular mound of florets (spiky things) in the middle. Ray florets (what I would call petals) surround the disc in the center. As the disc grows, the rays bend and seem to wilt. The coneflower looks more and more like a thistle and less and less like a flower. As you can see (maybe), it is beautiful – but once the petals bend back and down, its time, like the oak tree in my front yard, has come. I made the conscious decision to end my career as a synagogue rabbi as I entered my 35th year in the profession. The affliction that made that decision necessary began many years earlier, and there was no cure for it. The fatigue – physical, emotional, spiritual – that stressed my limbs and my relationships crept in earlier each year and lasted longer. Sabbaticals, scheduled for three months every four years, did not come often enough. My prayer life was shot. My age became an issue for some people. My ability to care for the people I loved to serve was waning, and they deserved what I always gave them: full-throttle attention and being treated as if their life-cycle moment or religious question or spiritual challenge was as fresh and compelling for me as it was for them. And I did not find much sympathy for my struggles from some key players in my wider professional world. I decided – with some loving honesty from my family – to stop while I was grizzled and before I became dangerous. But I had to have my coneflower moment before I could recognize that this phase of my life needed to conclude. It came during Yom Kippur in 2011 (5772, if you are using a different calendar). I wish I could say it was a spiritual epiphany motivated by the liturgy. (That happened three years later thanks to the gorgeous services at the Jewish Theological Seminary.) It was, instead, the explosion of love that found its way into my two sermons. In the evening, I spoke about the role of music in our lives and our worship. Woven into my words and concluding the sermon was Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah.” The cantor, whose talent and leadership opened my heart to the message, concluded my words by leading her a cappella group and the congregation in a soaring rendition. The next day I spoke about dying. In the course of pleading with the people in front of me to spare their loved ones the anguish of sussing out their end-of-life desires from medical directives and powers of attorney, I recreated a conversation with my own patient and loving family about what would make my life worth continuing in a final decline. I can say confidently it changed my life; I have been told that at least some others felt the same. You might expect that all those years in I would take a deep satisfaction that the old boy still had it in him. But, in fact, as I look back I can see that the petals had curled back and the thistle was emerging. I had held nothing back because, somehow, I knew I didn’t need to save anything for the next season. My doctor tells me I am healthy and my wife tells me I am happy and I can confirm both diagnoses. What fell away from me was the professional infrastructure any congregational rabbi needs to maintain as part of the job and as part of his or her personal life. Knowing when it is time to turn that over to younger blood is another one of those things they never taught me in seminary. Somewhere down the road in this blog likely will be a discussion of what it was like actually to leave the position. But the first entry was about the beginning and the second entry is about the end, so for a long time, you’ll be hearing about the middle.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI spent 35 years in the pulpit and learned a few things about the people and the profession Archives

July 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed