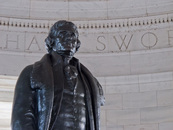

Sometimes a person offers an insight that is more profound than intended, even if it pretty remarkable on its own. My favorite example is from the Declaration of Independence. When Thomas Jefferson held this truth to be self-evident, “all men are created equal,” he could not have been aware that eventually it would do away with slavery, give women the vote, lead to the Voting Rights Act, result in the Americans with Disabilities Act and underpin the Lilly Ledbetter Act. But it did. On the other hand, sometimes a profound insight has a limiting effect. In 1996, James Carville encouraged the members of the (Bill)) Clinton campaign team to stay focused on three basic messages. One of them was “The economy, stupid,” later to become “It’s the economy, stupid.” The emphasis on economic concerns, usually reduced to jobs and taxes, has gotten in the way of more nuanced and sophisticated discussions of complicated issues in subsequent campaigns. This 2016 presidential campaign is no different in that respect. The contest to capture disaffected voters has focused from the beginning on jobs and taxes. Immigrants are taking our jobs. Wall Street is not paying its fair share of taxes. Globalization has destroyed formerly dependable employment. The infamous 1% controls it all. Many is the time I looked for a phrase that would capture my discomfort with placing a dollar value on what constitutes the United States and its blessings. And then I discovered it. The phrase is this: A country is more than an economy. I will leave it to you in the end to decide whether the context is profound or limiting. I guess it depends on how it is applied. There is no economic value to many of our freedoms. Yes, a clever advocate can make the case that the long-term neglect of certain kinds of regulation would a negative impact down the road, but most of the basic freedoms in the Bill of Rights that undergird our civil society are not economic in nature. An unfettered press does not necessarily create more jobs than a controlled one, even if “free” in this case does not mean without cost. But people have not immigrated to America seeking easy prosperity. Go to Hong Kong or a country moving from communism to free market for that. Go to Sweden or England for social welfare. Housing, food, transportation, higher education – all of them are cheaper somewhere else. It is the context of America that people are seeking when they come here. When my Jewish ancestors came from Eastern Europe, they were indeed seeking the “goldene medinah,” the Golden Land. Maybe they thought the streets were paved with gold, but they discovered what the 17th-century European migrants accidentally created: the land of the free. They discovered that a country is more than an economy. In spite of their initial poverty, in spite of the resident bigotry they encountered, they mostly never decided they made a mistake. No one in my family ever went back. And that’s the America they bequeathed down the generations to me. It is the one that measures the goodness of a societal trend by how many more kinds of individuals are welcomed into the tent of civil rights derived from self-evident truths and unalienable human rights that formed the foundation on which rest the blessings of liberty. A country is more than an economy. So it is a little frightening to know where I discovered this phrase. It comes from Stephen Bannon who was, until last week, running Breitbart (a very right-wing media company) and hosting a morning radio talk show for them. Since last week, he is charge of Donald Trump’s campaign for President. And this conversation reportedly took place on his morning show during the primary season: Last year, in a November interview with Bannon, Trump regretted the loss of a worker who took his skills back to his native India. “We’ve got to be able to keep great people in the country,” Trump said. “We have to be careful of that, Steve. I think you agree with that, Steve?” Bannon did not. “A country is more than an economy,” he retorted. “We are a civic society.” In a nut shell, Mr. Bannon’s comment sums up both the ethos of the campaign he hopes to run and the decision each voter has to make. The last word in the Trump campaign slogan – again – casts a longing glance back to a time when presumably white Protestant men were in charge. You could be any race, religion or ethnicity, as long as it (at least seemed) white and Protestant. And you could be either sex, except one. In fairness, that’s the goldene medinah in which my great-grandparents landed. It worked pretty well for many white Protestant men, like Mr. Trump. Until that tent expanded (and still in many ways) it didn’t work quite as well for anyone else. Promising people the chance to earn more money, the vocabulary of business people looking for investors, has nothing to do with expanding the tent. A country is more than an economy. If there is a continuing lesson for me in this political season it is how much “traditional Republicans” love this country and what it must become. The disruptors on the left, as much as on the right, hold to a fantasy that serves themselves to the disadvantage of others. The America that is a zero-sum game is one that preserves or bestows privilege. The civic society that operates, as some Republican once said, with malice toward none and charity toward all, is the one that expands the opportunities that keep us moving forward. Some of that has to do with jobs and taxes. But a country is more than an economy.

0 Comments

It was close to thirty years ago when I first faced an almost unbearable emotional pivot as a rabbi. A legacy family in our congregation had scheduled a naming ceremony for the first child of the next generation for late Sunday morning. And just a few days before, a brilliant, beloved and very young father died suddenly, leaving behind a devastated wife, two little children and a stunned community. I can still recall the feelings as I walked from the exquisite joy of the celebration to the crushing sorrow of the funeral. Perhaps I walked fifty steps. My insides were in turmoil; the tragedy of the death could not dampen the joy of the birth, and the giddiness of the celebration could not mitigate the catastrophic loss. I have had those experiences since. I can see now how the need to be fully present for others in each circumstance took its toll on my own inner life. But, hey – that’s the role of the rabbi. And, after all, though I am no less entitled to my feelings than anyone else, neither that naming nor that funeral had anything to do with my feelings. There were parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles awash in the miracle of life, and there were parents, children, siblings and a spouse for whom normal would never again be normal. They gathered within earshot of each other, but the tears they shed were from different wells. My role (I can’t really call it a job) was to take care of them. Those pivots certainly did not happen daily, and rarely were they between such extremes. The space around them was filled with responsibilities of my position. There were worship services to conduct, lessons to prepare and teach, meetings to attend, programs to run, staff with whom to collaborate. A hundred small decisions had to be made for every large judgment call. The long-term health of our community depended on the aggregated actions of the people with whom I worked, but the defining moments were the ones in which my voice, my words helped people make sense of the extraordinary of their lives. Other types of clergy know how I feel. School principals and teachers likewise mark their days by the regularity of the school bell and the punctuation of the unexpected. But nobody knows this better than people in public office. If the polls are right, you probably look at that last statement with a jaundiced eye. Recent rhetoric has been focused on the unreliability of “politicians” to do their jobs and uphold our values. An incredible amount of energy has been put into denigrating the motives of anyone who has spent time in public service – legislators, jurists, responders, military leaders. There is a candidate in the heartland of America whose campaign ads show him firing automatic weapons and pledging to “take dead aim” at politics as usual. And at least one candidate in this bizarre election year has sustained a campaign that ignores policy in favor of personal insults. The day-to-day aspects of the job are indeed critical. But I want you to consider what you need from the people who represent you. Consider the judge who was outraged at the treatment received by an admitted shoplifter: she was denied pants for her trip from the jail to the courthouse. The judge fined her for the crime, but apologized to her and reprimanded the inhumanity of those who mistreated her. Consider the police officer who responded to the call about teenagers disrupting a quiet neighborhood with a raucous basketball game. He called for backup. The backup was Shaquille O’Neill. Consider the presidential nominee who looked at the devastation of Hurricane Gustav and decided human suffering needed more attention than his campaign just as his nominating convention was set to convene. Consider the president who participated in the silliness of a correspondents’ dinner that interrupted the deadly seriousness of covering the events of the day. The event of his day was a high-risk operation to bring a murderous terrorist to his end. It wasn’t mentioned at all during the frivolities. Those are the pivots a leader must be able to make. To be a leader means to put aside the self-indulgent considerations to which everyone else is entitled. The leader must not turn away from the challenge. The leader must turn into it. When everyone else averts their eyes, the leader looks directly. When everyone else hands off to the next guy, the leader takes hold. When everyone else asks, “what about me,” the leader asks instead, “what about you; what do you need; how can I help.” I have had the unlikely privilege to meet many people in public service -- legislators, jurists, responders, military leaders. They are far from perfect, but the better they are at their mission, the more likely they are to acknowledge their flaws. Conservative or liberal, Republican or Democratic, faithful to a religion or devoutly secular, they accept that the needs of the people supersede their own. They have been entrusted with authority and sometimes with power and they want to use it well. They fall short and they see others fall short. The good ones respond with compassion. The selfish ones respond with attacks. As I write this, Phoenix, Arizona is washing away. Southern California is burning again. Hundreds of thousands of displaced persons have fled from wars in which they have no stake. African American parents are pleading with their children not to act like normal teenagers. Jews are feeling betrayed by old allies. Muslims and Hispanics are concerned about keeping their families intact. Leaders will pivot into the problems. Others will worry about their own injured feelings. Thanks to A.M.  Many times in my 35+ years as a rabbi I have been asked to "pray over" some sort of public convocation. I admit to being of two minds. On the one hand, this very Protestant tradition is ensconced in American life, and so it behooves those of us in the clergy to learn how to do it in an inclusive and appropriate way -- one that reflects our own religious integrity but does not deliver the message to segments of our increasingly diverse society that some of you just don't belong. On the other hand, I agree with a friend who is a federal judge -- public prayer has no place in the proceedings of government. A partisan political convention is a peculiar hybrid. It is technically a private affair, but it seeks to steer the course of government. I have volunteered many times to be a part of the invoking and benedicting of occasions such as the conventions. I like to think I do it pretty well. I have been privileged to receive invitations to participate numerous times (my first time in Washington was for a gathering of Jewish Republicans; I shared the bill with Henry Kissinger, Jean Kirkpatrick and Haley Barbour -- just us four. The treat of the day was hearing Chairman Barbour correctly pronounce "Agudas Achim" after much coaching.) In spite of many attempts over many months, I did not secure an invitation to attend, let alone participate in, the Republican National Convention this year. If I had, I would have said something very similar to the prayer I offered at the interfaith gathering the day before the Democratic National Convention (with language from the Republican platform, of course). The theme, by the way, was "pursuing love and kindness." My remarks: In the spirit of this gathering, I invite you to join me in reflection. Those of us who profess a faith in community call upon our Creator by many names. Those of us who profess an individual faith seek a name upon which to call. Those of us whose faith is in the better nature of humanity call upon those internal resources that inspire them. In the end, every call is issued in the hope that we are made vastly stronger and richer by faith in many forms and the countless acts of justice, mercy, and tolerance that faith inspires. Those words appear in the platform to be considered in the hours ahead, but they are true independent of any vote or acclamation. My tradition, the Jewish tradition, instructs us to pray for the welfare of the government, explaining that the authority it wields keeps us from consuming each other alive. Where there is no respect for government, where the rule of law is replaced by the anger of the mob, our opponents become our enemies, our enemies become our demons, our demons become our leaders. And instead of e pluribus unum, instead of a unity out of the many, we become suspicious of any difference, turning on each other and fleeing in fear at the sound of a driven leaf. But a good government, that is a government which IS good and which DOES good, a government envisioned by our Founders and established by we, the people of the United States, a good government deserves respect, demands respect, inspires respect. How, then, shall we ensure a good government, one for whose welfare we continually pray? First and foremost, by the pursuit of love and kindness. Those are qualities that create a beloved community, one that cherishes every life. Love and kindness create togetherness when they bring our collective strength in support of those who need it most. Good government, for whose welfare we continually pray, is one that seeks peace and pursues it. The Torah, our sacred Scripture, demands we call for peace even in wartime, that diplomacy is always the first option to create togetherness even with those we oppose. Good government, for whose welfare we continually pray, is one that does not claim that any group holds privilege over another. My tradition, the Jewish tradition, shares the teaching with Islam that humanity is descended from a single set of parents so that no one may say “my ancestors were greater than yours.” Creating togetherness honors every member of the human family. So as we move forward into this second set of political deliberations, let me offer words of prayer I hold for those of every faith and no faith, of every party affiliation and no party affiliation, for those who will vote their principles and those who will vote their interests: May it be the will of the one who gives of the divine glory to mere flesh and blood to bless us with good leaders – leaders who ARE good and who DO good – who honor every member of our diverse family, who are strong enough to seek the peace, and who, through love and kindness, will guide us in creating togetherness. May we, the American people, thus be inspired always to pray for the welfare of our government. |

Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed