weekly column

|

Each week, find a commentary on something connected to verses of Torah or another source of wisdom

|

|

Each week, find a commentary on something connected to verses of Torah or another source of wisdom

|

The Genesis:3 Project And I will make you swear by the Lord, the God of heaven and the God of the earth, that you shall not take a wife for my son from the daughters of the Canaanites, among whom I dwell. Genesis 24:3 The brand of religion in which I have lived my life is called Conservative Judaism. Honest, we had that name before it became associated with hyper-partisan politics, but that fact does not change the fact that we have no more chance to explain it than a contemporary high school sociology teacher has to place the nickname “Gay Nineties” in the context of 19th-century English usage. Oh well. The name was chosen because we wanted to conserve the essence of traditional Jewish life in the new era of American social liberalism. We resisted efforts to re-form or re-construct all of Judaism, even as we declined to adhere to certain orthodoxies. If all of that sounds like a lot of word play, let me make it worse by reminding you that English is not the native language of Jews and Judaism. But the fact that the division of Jews into categories is defined by anglo-nuance is an indication of just how thoroughly we embraced American culture. Until sometime in the last quarter of the last century, the intermarriage rate between Jews and others was tiny, so much so that the late Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan lifted it up as one of the secrets of Jewish vitality. (He wasn’t Jewish, just FYI. I tell you that because an Irish name is no indicator of religion these days.) Now, just a generation later, intermarriage is not only no longer an anomaly, it is the norm. Fewer and fewer Jews marry Jews every year, though the percentages of in-marriages are greater the more cloistered a life the Jews in question live. That is, someone who refrains from work and commerce on Saturday, eats only kosher food, studies sacred text in the original languages and lives within an easy walk of a vibrant synagogue is much, much less likely to marry someone for whom those deep faith commitments are not integrated into their daily life, even if they drink the same beer, root for the same sports teams and vote for the same candidates. But the number and percentage of Jews close to that end of the immersion spectrum has declined and will continue to decline by all predictions (except for some orthodox predictors). Is it a bad thing that Jews intermarry? From the time of Abraham, through the social revolution of Ezra the Scribe, through the expansion of dietary strictness of the rabbinic sages, through the dispersion of tightly-knit Jewish families into the expanding outposts of trade and culture, through the tentative opportunities for entry into enlightened societies to Senator Moynihan, the answer was a clear “yes.” Even today, when Jews and their non-Jewish partners are warmly embraced (okay, not always warmly) by Jewish families, it is rarely a matter of indifference to Jewish parents if their children marry other Jews. I will own it – it is not a matter of indifference to me, and not just because as a Conservative rabbi I am obligated to hold to that position. But the dire predictions of a catastrophic collapse of Judaism if we let too many of “them” in has not come to pass. Jewish life is different now, to be sure, and some of it has become unfamiliar across generational lines. But it turns out that Jews mostly like being Jews and that their life-partners love them not despite their Jewishness but, at least in part, because of their Jewishness. Who’d’ve thunk it? Both the umbrella organization of Conservative-identified synagogues and the association of Conservative-identified rabbis are reconsidering their stances on intermarriage and the families that are formed when one takes place. Should they be welcomed, and if so, how? Are there litmus tests that distinguish a new iteration of Jewish family from a purposeful exit from the community? Should a rabbi, representing Jewish authority, officiate at such a wedding? (Still no.) May the rabbi attend the ceremony as a guest? (Technically no.) May the rabbi wish the couple well? (Yes…carefully.) It is easy to attribute this reassessment to the purely practical. If we chase away our children, we have no future, some say. Better to take them in on their terms than to lose them on ours. That’s a defeatist attitude, and not how I choose to reflect on the question. Abraham had no confidence that his son Isaac – the only Hebrew of the next generation, and not exactly a firebrand – would carry forward an iconoclastic innovation if he was surrounded by a majority culture unfamiliar with his new heritage. Abraham made his servant swear to keep it all in the family. But more than three millennia later, we who are the heirs to the chutzpah that confidently conserved (or reformed or reconstructed) Judaism either believe it worked or it didn’t. If our conservation worked, then the matter of intermarriage is an opportunity, not a threat. If it didn’t, then we will not correct with authoritarianism what we could not accomplish with persuasion. I know that I am framing this issue differently than usual. The desirability, even the sanctity of the Jewish family is the usual starting point. I still believe that about the family, and I believe that Jews believe it overwhelmingly as well. Family is not the question. But sanctity? Unlike in Abraham’s time, that takes more than an oath.

1 Comment

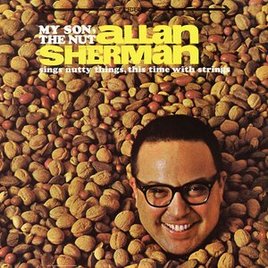

The Genesis:3 Project Abraham rose early in the morning, and saddled his donkey, and took two of his young men with him, and Isaac his son; and he split the wood for the burnt-offering, and rose up, and went unto the place of which God had told him. Genesis 22:3 I have heard God speak to me. I was bedside of a stroke victim along with his family. They were about to comply with his advance medical directive to discontinue life support. At my request, before the doctors shut down the ventilator, the adhesive tape that had been placed over his eyes and around the tube were removed so that his face was visible to his children and grandchildren. Most of them were speaking lovingly to the gentleman throughout the difficult moments. Only an adult son was silent, clearly overcome with the circumstances. As the doctor placed his hand on the knob that would shut down the machine, I understood what I was supposed to do. It was not a thought – I have been in enough fraught circumstances as a rabbi to know when my mind was working to find a response to the situation. I said what I “heard” myself say a split-second before I said it. Speaking to the silent son, I said, “Tell your dad to open his eyes.” The son said, “Dad, open your eyes.” Dad opened his eyes. The doctor responded in two affirming ways. The first, obviously, was to withdraw his hand from the ventilator (frankly, as if it had suddenly become extremely hot). The second was to say, “It’s a miracle.” I am not a mystical kind of guy. I know people who believe that they have regular conversations with God, or that God answers their prayers verbally or that, like Abraham, God called to them and gave them instruction. I never argue, despite my skepticism, especially since my own little miracle. But I do wonder with some frequency what I would have done if I perceived God’s voice instructing me to do something that was not so life-affirming as extending a stroke victim’s time on earth. Would I rise up early, split the wood, load up the car, wake up the workers, put my son into the front seat and drive off to an unknown destination with the intent of sacrificing him? My son will be relieved to hear I would not. And I want to add that not only would I not do so to my son, my only son whom I love, but I wouldn’t do it to my daughters or to anyone else’s child either. This story has been the subject of sermons, commentaries, expository legends, philosophical treatises and fictionalizations for thousands of years. I don’t know that I have anything original to add. But this verse – like the story of the climb up the designated mountain that “God had told him” – slows the action down to a glacial pace. The three-days’ journey that separates preparation from arrival is dispatched in a few words. The early-morning preparations are described in excruciating detail. Anyone who has packed for a three-day road trip knows that it is not like a run to 7-11 for milk and eggs. There was time to consider the consequence of that instruction. One of the many ways to consider this story is from the outside. That is to say, it is possible to dismiss the instruction to Abraham as the fantasy of someone (temporarily?) out of his mind. All of the aforementioned struggles with this story accept the notion of God and of God’s capacity to test Abraham with this unconscionable challenge. Indeed, I am at a loss for words that satisfy me when I am asked by my non-theistic friends how I can believe in such a God. I recognize the choice I make when I attribute benevolence to my little miracle and demur on Father Abraham. But having done that, I try to take away a contemporary lesson. Voices much closer to earth than the Holy One call on us to sacrifice our children in the name of devotion to a principle. The enemies of compassion ask us to allow our young people to travel to a distant place, geographically or morally, and explode themselves in the name of a cause. Others dress in business suits and attach dehumanizing names like “illegal” or “radical” or “elitist” to those who are worth less than devotion to a distant promise of greatness. I might have been forgiven if I had not heeded that sudden voice of God. Almost always, after all, doctors know best. The man recovered from his stroke…and had another fatal episode three months later. Nobody regrets those three months. They were an unexpected, life-affirming gift. But it is a slow process to recruit a true believer who will relinquish compassion and common sense for the promise of being a part of something larger. It is a failure of the recruit not to consider the consequence of a bad choice. Abraham got lucky in the end. But he got lucky because the voice that sent him on this fool’s errand stopped him from completing it. Others are not so lucky.  The Genesis:3 Project And Abraham called the name of his son that was born unto him, whom Sarah bore to him, Isaac. Genesis 21:3 Alan Sherman was a song parodist and comedy writer who entertained a generation of post-war grownups and inspired at least one generation of pre-adolescent boys. Weird Al Yankovic acknowledges Sherman as master of the oeuvre, and maybe just maybe I committed the entirety of “My Son the Folksinger” and “My Son the Nut” to memory. At 11 years old, neither “St. James Infirmary” nor “You Came a Long Way from St. Louis” were part of my musical repertoire, but I could sing the Alan Sherman versions as if they were. Even if the genre was not to your liking (or if Alan Sherman’s untimely demise preceded your birth), you have been unable to escape his most commercially successful parody, “Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah.” The lyrics are set to the delicate “Dance of the Hours” by Amilcare Ponchielli. The composer died in 1886, so we have no way of knowing if he would have been delighted or horrified to know that his lilting melody was better known as a paean to ptomaine poisoning than it was as a ballet. Then again, its previous popular iteration was an animated ballet of hippopotami in Disney’s “Fantasia.” (Alan Sherman also wrote a parody of “What Kind of Fool Am I” entitled “One Hippopotami.”) If you went to sleep-away camp in 1963 or later, “Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah” was part of your life. Alan Sherman was a writer whose talent was much more sophisticated even than his puns and politics in his music. His memoir, A Gift of Laughter, is a wonderful read. The stories he tells are not always happy, but they are touching and very well-told. He was a fat kid who was teased about his body, and he was a fat adult who was expected, ironically because of his success, to be the jolly fat man. The gift of laughter helped him through. Laughter became important to Sherman because it contrasted with so much of his life. In a lot of ways, he lived an unhappy version of what his contemporary Sam Levinson experienced. Family and neighborhood provided Levinson with abundant material to turn him into a “humorist.” Family and neighborhood were inconsistent in Sherman’s life and his ability to laugh and to make others laugh became his redemption. We place a lot of value on laughter in our time. Comedy is an industry, one of the very few that Jews don’t mind being accused of dominating. The vaunted “Jewish sense of humor” is one of those things that non-Jews admire most about the Jewish people, and it is often cited as our best defense against persecution. “As long as you can laugh…” begins and ends lots of anecdotes about the equally universal belief that it’s hard to be a Jew. The fact is that the Jewish sense of humor is something read back into our culture. Bilaam’s talking donkey, Queen Esther’s melodramatic, “If I die, I die,” Jonah’s description of the animals of Nineveh dressed in sackcloth are funny only because we have decided they are. They are not included for entertainment value; if there is laughter associated with them in the original, it is rueful, not hilarious. Back in the day, Jews weren’t any funnier than anyone else. Maybe Sarah had a bit of sense of humor about herself, but Abraham, our founder and mentor? Only one laugh – and it’s not funny. Isaac’s name in Hebrew (Yitz’chak) is usually associated with laughter. That’s entirely accurate, and in the context of the story of his conception and birth it makes sense. When Sarah is told that she would bear a son long after the evidence of her fertility was just a memory, she laughed (inside). Maybe she told Abraham and maybe she didn’t, but he gives his son a name that makes his heritage something of a joke. If it were a vaudeville routine, “What’s your name, friend?” would be answered, “You’re gonna laugh.” And Isaac did not live a life filled with laughter. He was neither Alan Sherman nor Sam Levinson. I love comedy and I love laughter. Every now and then I even produce a funny comment of my own. But I have learned that while I love to laugh and to make people laugh, sometimes (and maybe usually) that laughter comes at someone’s expense. Alan Sherman made fun of his weight for the sake of humor, including a signature monologue, “Hail to Thee, Fat Person,” but he died young from conditions connected with obesity and poor health habits. I saw him perform it on the TV special he hosted in 1965. It led him to a semi-serious conclusion that as a fat person he appreciated the word “ubiquitous.” He explained that it meant everywhere, unavoidable, all over. “This show is ubiquitous,” he concluded. “It’s all over.” So is this column. The Genesis:3 Project

God came to Abimelech in a dream of the night, and said to him: 'Behold, are going to die, because of the woman whom you have taken; for she is a man's wife.' Genesis 20:3 I just heard the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development say that the slaves of colonial and ante-bellum times were immigrants who came to the North America in the bottom of slave ships and dreamed of a better life for their children and grandchildren in this land of opportunity. And they worked hard for less in order to make that happen. As Dave Barry says, “I am not making this up.” I am not sure exactly how many things are wrong with Secretary Dr. Carson’s revisionist approach to slavery, but it helps to illustrate how difficult it is for some folks to face basic facts that are inconvenient. And when they have a platform to expound on their nonsense, it is sometimes enough to make me wonder whether I have things mixed up in my own mind. I know I have written about this dilemma before, but when I looked at the verse that frames this column, I knew that I am not immune from rationalization and justification myself. Abimelech, local king and frenemy to Abram, cast his eyes upon the beautiful Sarai who was Abram’s wife and, like any self-respecting king, he took her into his household. His intentions were carnal in nature, but his good luck was that he waited a night before pursuing his desires. In his “defense,” he was informed that Sarai was Abram’s sister, not his wife, and in a scene anticipating the end of the movie “Chinatown,” Sarai ‘fesses up that she is sort of both. In the middle of this mess comes this verse to tell us that God appeared in a night-dream to protect the honor of Sarai because she is another man’s wife. Actually, the phrase “man’s wife” is nowhere near that gentle. There nearest I can come to a family-friendly translation is that Sarai was “mastered by a master.” Use your imagination. Reading contemporary sensibilities back into a text that is thousands of years old is dishonest if the desire is to understand the text in its own origins. In a society that assigned a formally subservient role to women and validated the privilege of men to acquire them based on a hierarchy, the story of Abram and Sarai playing a little con game to save both of their lives may seem admirable, and God’s intervention affirms Abimelech’s noble(-ish) intentions…in the original context. But imagine if you can this scenario as justification for the treatment of any human being. Maybe it is the plot of a “Law and Order” episode, but in real life it is sex trafficking. Instead, the night-dream of Abimelech helps us understand the nightmare of all the Sarais in the world. The lessons we draw from it as the inheritors not only of the Biblical text but also of human experience include the unacceptability of “taking” another human being and how certain standards – beauty, privilege, self-preservation, “mastery” – can and should be replaced. Sarai was not a free-spirited vixen in an open marriage, pushing the boundaries of sexual propriety and worming her way into a position of power by playing on the emotions of a libidinous potentate. She had no choices. Back then she was a human being assigned a status, and back then that status was defined by her relationship with men. In other words, she was not a free agent, she was not a partner in her marriage and she was not a tourist who came along for a ride on Abram’s caravan looking for adventure or a better life. She was enslaved. What was legal and even moral in those olden days is not justifiable according to the values that have evolved from people who read the Bible for moral growth rather than for self-justification. Which brings me back to a man who is a brilliant surgeon but otherwise, forgive my incivility, a blithering idiot. A person taken by force and transported across an ocean to be sold as free labor is never, never, never to be called an immigrant. Immigrants choose, by desire or circumstance, to relocate. There is no choice in slavery. “Taking” another human being is unacceptable, and though the stories of struggle and resistance by individual slaves provide an insight into the human spirit, they do not constitute a lesson in how hard work for low pay is worth it if your children and grandchildren enjoy a better life. Ever.  The Genesis:3 Project He urged them mightily, and they turned toward him and came to his house, and he made them a feast, and he baked unleavened bread (matzos), and they ate. Genesis 19:3 If you are looking for full-time work, think about trying to figure out the current senior advisor to the President, Steve Bannon. There are more versions of this man than there are of “Santa Claus is Coming to Town” on an all-Christmas music radio station. He’s been a puppet, a pauper, a pirate, a poet, a pawn and, seemingly now, a king. If you want to begin your research, there are any number of profiles of him from a variety of sources, some more reliable than others. But his recent affirmation that the main goal of the current Cabinet is the “deconstruction” of government caught my attention. If I wanted to be suspicious, I would compare deconstruction to reconstruction, the efforts of the victorious United States government under Andrew Johnson and Ulysses Grant to put the South back together again after the Civil War. Mostly, the Reconstruction fell short of its goals; it was successful in some areas and less successful in others, but it certainly did less than the minimum for the freed slaves of the defeated Confederacy. Still, when I hear “deconstruction,” especially from an educated and sophisticated man like Mr. Bannon, I hear a distant banjo playing “Dixie” and smell the magnolias in bloom. I have written before about the “again” in “make America great again.” So much of what the President intends by that phrase is sheer nonsense. For example, manufacturing jobs will not be coming back, not because of globalization, but because of automation. Three guys and a smart phone can build a car in a robotic factory that used to employ thousands. But the part of “again” that appeals to many Americans – white, Christian, living in the heartland – is from that time when certain presumptions the ways things were supposed to be went unchallenged. People had manners. They spoke English. They went to church. They knew their place. I wish I was in that America – old times there were not forgotten. Those days before rebellion and that hopey-changey thing were comfortable. No person of color or immigrant would get a leg up to take what was presumably mine. It sounds like I am calling an entire swath of America racist. Forgive me. I leave it to others to use that word if it is even appropriate. I would suggest that they have been seduced by a false nostalgia that is selective in its presentation. Mr. Bannon and his ilk suggest that they are hearkening back to better times when things were the way they were (here’s the important word) originally supposed to be. This notion that the way I remember the good things in my life is the way they were meant to be is natural for human beings, but it isn’t accurate. Unlike the academics and legal scholars who try to figure out the original intention of a document or law (which in and of itself is only part of any consideration), the purveyors of false nostalgia are inherently dishonest. There is no identifiable starting point for society or culture, and values and practices have always been in flux. When President Eisenhower was a little white Christian boy in the heartland, he never heard the term “military industrial complex,” and if he were alive today (at 126) he wouldn’t recognize the phenomenon he named. Ozzie and Harriet Nelson did not grow up with Ozzie and Harriet as parents, and their son Rick wound up disillusioned and addicted in spite of actually having Ozzie and Harriet as parents. But, boy, is that false nostalgia seductive. Which brings us to the verse of the week. Lot (the “he” in the verse) baked for the visitors (“them”) unleavened cakes of bread, commonly known as maztot or matzos. Some of the commentators suggest that he did not wish to keep them waiting for bread to rise, so he provided this sort of crispy flatbread to his reluctant guests. But there is one commentator who reaches a different conclusion. His name is Rabbeinu Asher and he is a deeply honored scholar from 13th-century Spain. In fact, he compiled the code of Jewish law still considered foundational eight centuries later. Why did Lot serve his visitors matzos? Because, says Rabbeinu Asher, it was Passover. Rabbeinu Asher did not have a screw loose; he believed that the holidays he loved and celebrated in Toledo in 1237 were the same ones our people had always celebrated, and in the same way. You don’t have to be an historian of religion to know he is wrong; the Bible itself tells us that Passover commemorates events that happened hundreds of years after Lot was dead. Reading current practice back into history validates who and what you believe about the world. Deconstruction – clearing away all of those pesky agencies and regulations and appointees who are obscuring the original greatness of America – comes from the same place that presumes Lot conducted a seder in Sodom or Gomorrah. It’s a lovely fantasy, but a fantasy none the less. So when Mr. Bannon suggests that we want to return to the old times that should not be forgotten, pay no attention. Look away. Look away. |

Archives

October 2023

Categories |