weekly column

|

Each week, find a commentary on something connected to verses of Torah or another source of wisdom

|

|

Each week, find a commentary on something connected to verses of Torah or another source of wisdom

|

The Exodus:5 Project The LORD said to Moses, “Say to the Israelite people, ‘You are a stiffnecked people. If I were to go in your midst for one moment, I would destroy you. Now, then, leave off your finery, and I will consider what to do to you.’” Exodus 33:5 There is a remarkable school just outside of Tel Aviv called the Shenkar Institute, a university-level school of engineering and design. I have mentioned it in other places, but I highlight it again because I have been surprised at the role fashion plays in this book of the Torah. When I say fashion, I do not mean couture, of course, but the clothes people wear and what it says about them. And Shenkar has placed itself at the intersection of cutting-edge technology and how design expresses our values and tastes. My wife and I visited the campus some years ago and saw some of these projects in development. One of Israel’s daily newspapers had commissioned a competition to created furniture out of recycled newsprint. Some students had been assigned to imagine a household product and develop packaging and a marketing strategy for it. On that particular day, graduating students were showing their final projects – wedding gowns that were to reflect a past moment in Jewish history – to a panel of professional fashion designers. And the remarkable president of the institute, Yuli Tamir, showed us a textile that had been grown from bacteria. (Don’t say eww; it was both beautiful and astonishing.) Those of us of the male persuasion sometimes roll our eyes at the different focus many of the women in our lives have on clothing. I will suggest that it is a matter of degree, not substance. How we dress, why we dress how we dress, and how we decide why we dress how we dress (got all that?) communicates as much about ourselves to the world around us as any other choice we make. Clothing (and the right accessories) includes an element of the aesthetic, larger or smaller, but it also makes important statements about how comfortable we are in our bodies, what we intend to accomplish when dressed as we are and which other people we declare to be our cohort. Clothing can make a statement of our uniqueness, of imitation or of a desire to disappear into the crowd or the landscape. Of course, some clothing choices are not personal. Military personnel, medical practitioners, responders, sports team members and even fast-food employees wear outfits we call uniforms because they are designed to convey skill or authority, but not really individuality. The clothing is chosen specifically to represent a role that the person plays. Or, the depersonalization of clothing may have the purpose of depersonalizing the individual. Inmates in jails and prisons have sacrificed their opportunity to self-expression through clothing. In fact, the stripes or bright colors or larger letters “INMATE” on their clothing are specifically to place the imposed identity of criminal on them ahead of any other aspect. There is a presumption of how someone in such a uniform may be treated, and especially if person wearing those clothes is outside the place of confinement.

0 Comments

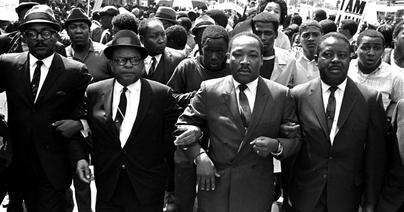

The Exodus:5 Project When Aaron saw this, he built an altar before it; and Aaron announced: “Tomorrow shall be a festival of the LORD!” Exodus 32:5 Perjury is a legal term for lying under oath. Because such an act takes place during legal proceedings, it is logical that the word and its behavior have been carefully picked apart by the people who are concerned with such things: lawyers and judges. Suppose a man was on trial for murder, the victim having been shot four times. If the examining attorney said to him, “Did you put four bullets in the deceased?” and the perp knows something the lawyer doesn’t – someone else shot one of the bullets – is it perjury to answer “no?” No. It could be that the prosecutor needs to prepare better. But it is also the case that careful examination of testimony in criminal and civil cases is the hallmark of an honest legal system. Though the rigid application of the specifics of the law may result in failings in the pursuit of justice in one or another case, such missteps (ideally) serve to hone the law to prevent such shortcomings (ideally) in future applications. The problem with the perjury standard in legal proceedings is this: life is not a legal proceeding. The person who crafts his or her words to carefully mislead with malice aforethought may or may not be legally innocent but is an absolute scoundrel. And our national discourse is filled with absolute scoundrels these days. They stand on the podium in the press room. They make the rounds of the talk shows, serious and satirical. They occupy the offices of secretaries and under-secretaries. They tweet. They make things up and sprinkle the dust of credibility on them so that when presented with the evidence of their fabrication they can scream “fake!” Martin Short plays a character named Nathan Thurm, a nervous liar who challenges everything said to him and eventually pleads to the camera, “Is it me or is it him? It’s him, right?” Bart Simpson made his early reputation denying responsibility for every mishap with an automatic “I didn’t do it.” And then there is Aaron. Jewish tradition has nothing but kind things to say about Aaron. Yet, the drama surrounding the Golden Calf was most certainly a failure of integrity on his part. Here he is on record declaring what is most certainly transgressive – Tomorrow will be a festival of the Lord! But when he is called on the mayhem that occurred on his watch, like the murderer who sees a loophole in the poorly-worded question, he gives the unmistakable impression that it was them, it wasn’t me. I didn’t do it. Aaron has many defenders among the commentators and the contemporary faithful. But there is no getting around the fact that he lied. It wasn’t exactly perjury, but it was most definitely not the truth. Handed the responsibility to maintain the blamelessness of the people through expiatory rituals, you might think Aaron is suddenly and permanently disqualified. If, on the other hand, you believe in second chances, it is worth remembering that Aaron remains blameless for the rest of his life, even when he might have been excused for reacting badly to the untimely deaths of sons and tribesmen. Perhaps this new path qualifies him in the hearts of our people for a do-over on his truthfulness despite the incident with the Calf. But our contemporary scoundrels seem emboldened by what they can get away with. As surely as we have a record of Aaron saying, “Tomorrow will be a festival of the Lord,” we have audio recordings, video in wide distribution, eye-witnesses and victims, all of which attest to deceit at worst, obfuscation at best. But they tut-tut their accusers, deny the record and insist with practiced umbrage, “it was them, it wasn’t me; I didn’t do it.” I admit to a soft spot in my heart for the defenders of Aaron. They wish to see the good in him and the best about him. They practice on him what he practiced toward others, to always give them the benefit of the doubt. If a single massive transgression had a purifying effect on Aaron’s honesty, I can even understand how some even deflect Aaron’s guiltiness by claiming he was trying to diffuse a time fraught with anxiety. But among our modern-day prevaricators and their supports there is no benefit due. The lies are intentional, often cruel and always delivered with self-righteous arrogance. And because, to this point, most of the lies go without significant challenge, it has set the standard for a nation. An entire generation had to pass before Aaron’s lie was no longer personal memory. Let us hope that despite these years of marinating in the constant flow of lies and “alternate facts” we find our way back to integrity.  The Exodus:5 Project to cut stones for setting and to carve wood—to work in every kind of craft. Exodus 31:5 Fifty years ago, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered the next-to-last public address of his life in Memphis. Speaking to members of the local union of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, he sought to lift them up in a city that weighed them down. The sanitation workers in particular heard themselves compared to doctors, probably for the first time. Without them, Dr. King said, disease would run rampant and doctors would be too overwhelmed to do their jobs. But it was not just the garbage collectors who received praise. Here is what else Dr. King said: So often we overlook the work and the significance of those who are not in professional jobs. But let me say to you tonight that whenever you are engaged in work that serves humanity and is for the building of humanity, it has dignity and it has worth…All labor has worth. In the various debates we have about jobs in this country, we often overlook the importance of work. The ability to master a job of any kind and perform it well is as important as receiving fair compensation for doing that job. Twenty-five years after Dr King’s speech, I entered a friendly debate with a friend who worked in the White House. President Clinton had added requirements to welfare that included the expectation that recipients would work. I had referred to it as the dismantling of the safety net. My friend insisted otherwise. “The way a person determines his or her worth is by work. It goes back to the very beginning of Genesis, when Adam overcomes his sin by the sweat of his brow. What we are doing for those who are able is not just giving them the resources to survive, but dignity in their own eyes and in the eyes of society.” I was persuaded. (He made me write it down and sign it.) Since that time, I have noticed more and more the truth of both teachings. The feel-good show with the hokey premise, “Undercover Boss,” highlights the individual employees of franchise corporations who master a small part of a large operation. Managers, wait staff, exterminators, janitors, parking lot attendants are all shown attempting to teach the CEO (in a disguise) how to earn what is often a subsistence wage. The six-figure salary of the boss is not an indicator of the skill necessary to take a fast-food order fast or pack a box securely. Some of these bosses look like Lucy and Ethel on the bonbon assembly line. Inevitably, the boss confesses admiration for the employee and makes a big show of a big reward that helps the struggling employee achieve a dream. I have seen the pride of chambermaids with limited English in hotels they cannot afford to stay at. I have benefited from the skills of the mechanic who cannot afford a car payment as he keeps my automobile running smoothly. The orderlies in the hospital wade into bodily effluence and clean it up quickly enough to avoid both infection and embarrassment. The taxi driver’s knowledge of the roads, the landscaper’s sculpting of a hedge, the security guard’s polite concern when a stranger arrives for an appointment – this is the dignity of labor. It is that dignity, that sense of worth that people seek when they come to the United States. Whether they come as they should, with permission, or as they should not, by stealth, overwhelmingly they are seeking to do something well and to earn what they need to provide for themselves and others. Almost none of them come here with malice aforethought or looking to initiate a criminal enterprise. They arrive instead with the belief that work in every kind of craft has worth, dignity or, as the Bible might suggest, holiness. Some folks whose work experience involves manipulating other people’s wealth pay lip service to jobs and look down from their towers at the poor and displaced. They do not understand the value of work, seeking to deny compensation to those who cannot meet the invented standard of an incompetent boss. It is no wonder that, despite their finessed wealth, they are regarded as undignified and without real worth. As the Dixie Chicks lamented about today’s country music, “they’ve got money, but they don’t have Cash.” But at least once a generation it is worth reminding ourselves of the dignity of labor, and that all labor has worth. It all serves humanity and is for the building of humanity and must therefore be honored and respected – especially because of the holiness of every set of hands set to it.  The Exodus:5 Project Make the poles of acacia wood, and overlay them with gold. Exodus 30:5 Do not read the rest of this column if you are offended by four-letter words and making fun of accented English. You are forewarned. Many years ago, during one of my congregation’s trips to Israel, I was talking with a guide outside of Eilat. He was about to lead us on an ATV ride through the desert (highly recommended) and was getting ready to tell these Americans what they would see. His English was as acceptable as my Hebrew, but there were certain specialized vocabularies he had yet to master. Eikh kor’im la’eitz hazeh ba’Anglit? he asked. (What do you call this tree in English?) Eizeh min eitz zeh? I replied. (What kind of tree is it?) Shittim, he said. Acacia, I answered. Lamah acacia? he asked. (Why “acacia?”) I was faced with a dilemma. The Hebrew and English names had nothing to do with each other, but the fact is that most American Jews are completely unfamiliar with the Hebrew name. A Hebrew folk song, sung primarily around Tu B’Shvat, the Jewish arbor day, takes its lyrics from a brief Biblical verse that means “acacia trees are standing.” The Hebrew lyrics are atzei shittim omdim. You simply cannot teach sixth-grade American children to say shittim over and over again, especially if the lyrics are set to a Latin melody most often accompanied by a conga line. So some tight-ass Hebrew school principal changed the words from “acacia trees” to “olive trees” and Hebrew school students in this country grew up singing atzei zeitim omdim. Apparently when it comes to parental outrage, changing the Bible is acceptable. Of course, there are classic stories that circulate among Jewish educators about Israelis who find their way to the US and commit their own profane faux-pas. They may be urban legends, but they are told (like all good urban legends) by people who swear they heard them from a reliable source. My favorite is about the Israeli camping counselor who instructed his charges to prepare for the upcoming overnight: Tonight, we slip on the bitch. If you don’t want to have sand, bring two shits. If your foots they get cold, bring sucks. And if you have allergies, let me know because we will eat penis butter. I don’t want to sound too smug, having entered a makolet (bodega) in Jerusalem as a long-haired young man looking for spices. Instead of using the modern Hebrew word, I mispronounced the last word of the blessing over the spices that end Shabbat and asked the owner for illegal drugs. I subsequently shopped elsewhere. It’s not just Hebrew and English that can offend each other unintentionally. My grandfather, of blessed memory, was wise never to go to Paris. A plumber by trade, he told people many times about the French plumber who greeted everyone with “Bum sewer.” German stores that sell jewelry advertise themselves as merchants of “schmuck.” And true or not, a Persian friend once told my wife that she wanted to find another name to call her because her name in Farsi meant…well, it sounds like acacia in Hebrew. Anyway, I had to answer the guide with something. So when he said, “Lamah acacia?” I paused a moment and decided on the only answer I could give him. “Lamah shittim?” He was satisfied. |

Archives

October 2023

Categories |