weekly column

|

Each week, find a commentary on something connected to verses of Torah or another source of wisdom

|

|

Each week, find a commentary on something connected to verses of Torah or another source of wisdom

|

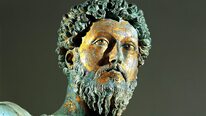

Wisdom Wherever You Find It The best revenge is not to be like that. Marcus Aurelius It was Henny Youngman who said, “A patient says to a doctor, ‘Doc, it hurts when I go like this.’ And the doctor says, ‘Then don’t go like that.’” I know better than to try to take apart a joke to see why it is funny. Fortunately, I have Marcus Aurelius to analyze instead. The quotation is actually in Greek, which means that I am working in translation. In my attempt to be certain was at least close to the original, I looked at a number of sources, each of which put the translator’s own little spin on the original. Most of them wanted the observation to sound more like Marcus Aurelius and less like Henny Youngman. But the one that splits the difference (by using archaic English) is this: “The best way of avenging thyself is not to do likewise.” In other words, if it hurt when someone did that, don’t do that. It may be a little heretical to say I like this version better than the aphorism that emerged from Jewish and Christian sources roughly at the same time in history. Jesus phrased it positively: Do unto others as you would have others do unto you. Hillel phrased it preventatively: That which is distasteful to you, do not unto others. (Disclaimer: those are also translations.) But Marcus Aurelius acknowledges what is really part of the human condition. People who have been wronged want revenge. Revenge is a peculiar emotion that has motivated bad history and great literature, but in the end it is imitative. The person who seeks revenge wants to preserve, even intensify, something hurtful and outrageous. In dispassionate moments, most people would likely come around to the notion that nothing but private satisfaction is gained by returning wound for wound, and even that satisfaction is short-lived. But in the throes of injury, especially when it is intentionally inflicted, the victim thinks from the place of pain rather than wisdom. In fact, the more popular translation of this Greek phrase is “The best revenge is not to be like your enemy.” By substituting the offender – presumed to be an enemy – for the offending behavior, the sufferer animates the pain by giving it a body and life force, which can then be eliminated or, for the principled Stoic, spared. It’s almost as if Henny Youngman’s patient replies, “You’re a quack, and I am going to give you a bad Yelp review.” Ruins the joke. The notion that the best revenge is to delegitimate the bad behavior is, to my mind, a huge step forward. I could say that unlike tit-for-tat, taking the high road gives me the sense that I am improving the world around me by modeling a kinder, gentler way to comport myself. I am not that noble. Rather, it allows me to feel smug, which is not a particularly admirable character trait, but it keeps me out of jail. Also, it actually does improve the world. Revenge may be organic, but it pollutes the human family the way carbon emissions make life more difficult for everyone. Whether you take your cues from Marcus, Jesus, or Hillel (or even Henny), the formula for living a good life is to reduce the suffering in this world, not only for yourself and those you love, and not only for people you never knew, but for the people who did you dirt. Might that latter group feel they got away with something and try it again? It’s a possibility, and maybe even a likelihood (if I am feeling a little cynical). The resolution to a grievance is the pursuit of justice, not revenge. I have plotted revenge many times in my life. If you don’t hold me to it, I may admit I attempted it once or twice. But honestly, all it does is renew the original pain, and what I always really wanted was for the pain to go away. That’s why the best revenge is not to be like that. Take my advice. Please.

0 Comments

Wisdom Wherever You Find It There were no formerly heroic times, and there was no formerly pure generation. It is a weakening and discoloring idea that rustic people knew God personally once upon a time – or even knew selflessness or courage or literature – but that it is too late for us…In any instant the sacred may wipe you with its finger…In any instant you may avail yourself of the power to love your enemies, to accept failure, slander, or the grief of loss, or to endure torture. Annie Dillard Nelson Mandela, Natan Sharansky, Wang Weilin, Ieshia Evans, Annette Goodyear. The names may or may not be familiar at first glance, but the reasons you should know them most certainly resonate. Within your lifetime, these individuals made the times we live in heroic by their actions. They are, in retrospect, remarkable, even exceptional individuals. In other times and other circumstances, they may have been ordinary and unnoticed. But, as Annie Dillard says, they were wiped by the finger of the sacred. They are products of our generation – not a pure cohort, certainly not rustic, and positively not an iteration of the human family that can claim to know God personally. At a moment in the natural course of their lives, each one responded to an opportunity that presented itself and refused to be overwhelmed by it. It was a choice, not an inevitability. Some went on to build on that moment and others disappeared into ordinariness. I admit to enjoying the achievements of other people. I find them inspiring. It prompted me to create The Sixty Fund, which irregularly awards a nice letter, a home-printed certificate and a small check (really small) to people I notice who display courage, compassion, wisdom, or generosity that might otherwise go unnoticed. Actually, to say I created it is not 100% accurate; my family gave The Sixty Fund to me as a 60th birthday gift, and it has turned into one of the best things I do. I have the chance to acknowledge people who were wiped by the finger of the sacred. Some of their stories will be told for generations while others will be discarded with the newspapers and expired online links that brought them to attention. But what is correct is that not a one of them – just like you and me – was born to be a hero. They were presented with an opportunity and found themselves without a real choice of how to act if they wanted to do the right thing. Countless others have faced similar chances. Some rose to the occasion and others responded to different impulses. A debate among rabbis took place many hundred years ago about Noah the ark-builder. The Bible calls him a righteous man “in his generation.” Was he righteous only in comparison to the general wickedness of his society, or would he have been considered righteous even among a community of admirable people? That is, in “his” generation or in “any” generation? The debate is unresolved, but the question is more important than the answer. In righteous times, Noah’s heroics would have been unnecessary. He would have been an ordinary man, even if he were among the righteous. Circumstances even in those allegedly pure and rustic times were what produced heroes who expressed selflessness or courage or literature. Writ large or small, you yourself have been that person when you otherwise had no choice – the comforting arms for a bereaved companion, the rebuke to a bully, the acceptance of responsibility for a hurtful mistake, the profession of love to a lonely friend, the endurance to power through pain – if you wanted to do the right thing. Your action was biblical, epic, legendary, emulable. It was not dependent on reportage. So many stories and teachings we call holy attain that status because they are distant and old. Did the people who lived them recognize their significance as they occurred? Maybe. More likely, no matter how close they felt to revelation or inspiration or holiness or achievement, they still fell short of their ancestors who lived in a formerly pure generation and more rustic times. They believed that the noise of contemporary society drowned out the primal connections to nature and creation that the Elders knew in their bones. They were as wrong then as we are now. Our lives attest to the potential for greatness. Especially in complicated times, simple survival is heroic. If our forebearers beat a path for freedom across the wilderness on any continent, then we and our descendants are no less the successful pioneers for navigating asphalt and technology. And if, when presented with a chance to rise even above the extraordinary fact of living every day, we do so by reflex or intent, then we owe it to ourselves and those insecure ancestors to acknowledge and give thanks for having been, in that instant, wiped with the finger of the sacred.  Wisdom Wherever You Find It To the Prophets, a moral infraction was a cosmic outrage. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel If you made a short list of modern thinkers who have inspired humanity, it would necessarily include Abraham Joshua Heschel. He lived his life at the intersections of existence – spiritual and practical, heaven and earth, human and divine, particular and universal, momentary and eternal. He was exquisitely exacting in expressing himself. His daughter Susanna remembers that he considered a successful day to be one on which he wrote a good sentence. This quotation must have made for a very good day. As with most of what he wrote, reading Heschel too quickly puts you in danger of missing the point. There is no incidental language in this sentence. An infraction is often a very minor transgression – in contemporary language it is used to describe illegal parking. A moral infraction sounds like a mere lapse in judgment, like not returning excess change from a small purchase or perhaps embarrassing someone with a casual remark. In fact, the person who commits an “infraction” may very well object to the notion that such a powerful word as “moral” is attached to it. But that is, I believe, Heschel’s point. The phrase “cosmic outrage” is loaded with power. If an infraction, moral or otherwise, is something one might excuse or overlook, there is no ignoring the explosive description of indignation writ large. Here is the intersection of the inconsequential and ultimate. And Heschel, who sought out those places of connection, invites you into the place where those concerns connect. Please don’t stop there because I do not want to overstate my case. This formidable assertion has a modifier. It appears in the introduction to the book that established Heschel as a voice of his generation, The Prophets. His examination of the Biblical prophets, individually and collectively, opened a window to the unique messages of each one and the ethos of prophecy. The prophets were not self-anointed orators. They were messengers, often reluctant, whose sensitivity to the divine presence provoked listeners then and down through the centuries to consider the way every person and every group of people (and especially the Jewish people) might live up to the sacred nature of being created in God’s image. That’s pretty old-fashioned language, but please remember that the Bible is an ancient collection. It is “to the Prophets” that the moral shortcoming was the source of divine anger. The prophets were our instructors, not necessarily our role models. To live at the intersection of human fallacy and divine rectitude, a person needs to know both. The first qualification is widely accessible. The latter is in scarce supply, and not something that any person can merely claim. Heschel and other believers in the Bible attribute the knowledge of God’s will to God’s will, not to human deduction. Prophetic teaching, which is not predictive (the modern sense of the word) rather instructive, is meant to make us sensitive to what Heschel called the “divine pathos.” The general lesson that Heschel describes is that our misconduct breaks God’s heart. Reading the Prophets with that notion in mind (in fact, reading all of the Bible with that in mind) casts the God of the Hebrew Bible in a much more sympathetic light than ancient and modern skeptics accusingly shine on the “Old Testament.” (An aside: “old” sounds much less pejorative to me now that I am old.) But here is the other lesson of Heschel’s teaching. Modern activists who lay claim to the insight of the Prophets almost always overstep their bounds. Those who confuse personal outrage with cosmic outrage commit their own moral infraction. Actions that purposely cause suffering to others, justified by the would-be prophets, cause divine heartbreak, not approbation. If Heschel could take great satisfaction in one carefully crafted sentence, we, his students, should be at least that deliberate in applying his lessons.  Wisdom Wherever You Find It May your homes not become your graves. High Holy Day prayerbook In the liturgy for the afternoon of Yom Kippur is a recollection of the long-ago service of atonement in the Holy Temple. At the end of the description of the sacrificial rituals is a tiny addition. The High Priest says to the pilgrims who have gathered from the Sharon Valley on the coastal plain, “May your homes not become your graves.” That section of the Holy Land is subject to earthquakes, and when they occurred the stone structures in which people lived could collapse without notice. In the liturgy, the prayer is just that brief, but even thousands of years later, thousands of miles away, hundreds of thousands of days since the last catastrophic earthquake, I am always captured by the poignancy of what feels like a spiritual afterthought. Of late, the prayer feels more immediate. The rash of violent natural occurrences that have produced unusual and ferocious tornados, volcanos and tsunamis, deluges, fires, and earthquakes each produces photos of the aftermath in which our homes have become our graves. There is barely a week that goes by in which multiple people do not lose their lives in collapse, explosion, fire, or asphyxiation in private or public housing, making our homes become our graves. The global reach of daily news brings constant shock over the homicides and suicides – most often by gunshot – of entire families, turning our homes into our graves. There is always an element of complicity in these tragedies by human hands – the ones that hold the firearms, the ones that do not maintain the housing, the ones have contributed to climate change. The prayer has a much larger metaphoric resonance as well. Eastern Europe was home to millions and millions of Jews (and other minorities) in the early 20th Century. Our homes became our graves. My goal is not to depress you, though I have probably succeeded, nonetheless. My goal is to illustrate how easily the specter of death can overwhelm the heart that needs to grieve and remember other hearts. Late last year, I lost a dear, dear lifetime friend who succumbed to a phalanx of health challenges that finally dominated a heretofore indominable spirit. As her family grieved, death paid another visit to her mother who was, no doubt, made more fragile by the death of her beloved child. Unbelievably, during the funeral for the mother, her mother-in-law died. The husband, my soul-friend, was bereaved three times in two months. No place he could lay his head was untouched by death. I am no longer the rabbi of a congregation. I like to say I am out of the retail end of the business, but old reflexes can come back pretty quickly. I was distressed for the family and for myself (almost a part of the family) that the circumstances had conspired to replace grief for each loved one with a sort of death-fatigue. Compassion for the survivors is important after any loss, but it is no less important than the respect that the distinct memories of the deceased demand. Three genuinely remarkable women had died so close to each other, and our natural inclination was to push against death, not to grieve the uniqueness of each. That’s the danger of that painful prayer: may your homes not become your graves. Of course we pray for that. Of course it is appropriate. Of course we do not want to conflate the place we live with the place we die. But the death of another is not our own death. It does not matter the cause – the Holocaust, the covid virus, the hurricane, the assault weapons. The life that death has claimed deserves our grief in a way that does not allow our fear of death itself to claim that life a second time. Death will successfully stalk each one of us, God willing for 120 years. And when we die, as we must, we deserved to be mourned uniquely, whatever form that takes. May our homes not become our graves. May death claim those we love only once. |

Archives

October 2023

Categories |