weekly column

|

Each week, find a commentary on something connected to verses of Torah or another source of wisdom

|

|

Each week, find a commentary on something connected to verses of Torah or another source of wisdom

|

The Numbers:13 Project These are the commandments and regulations that the LORD enjoined upon the Israelites, through Moses, on the steppes of Moab, at the Jordan near Jericho. Numbers 36:13 The other evening, as I relaxed after a long day, I half-listened to one of those breathless network “true-crime” programs. It reported on the tragic saga of a young man who committed suicide after being encouraged by his girlfriend. The correspondent went to great lengths to make both sides of the story sound equally compelling and succeeded at convincing me that two young lives had been wasted. Saddened though I was by this story, my attention was snagged by the defense attorney’s legal gambit. He was quite insistent that independent of the girl’s intentions and regardless of the contents of the electronic messages she sent to her boyfriend, the charges against her (involuntary manslaughter) were not legitimate because the law did not define encouragement to suicide as a crime. What he did not say, though he didn’t-say it very clearly, was that even if she were guilty of persuading this young man to end his life, her words were not a violation of any applicable law. I am not a lawyer, and any expertise I have in the law is from studying Talmud, but these fifteen seconds of legal justification struck me as infuriatingly wise. We sometimes decry the minutiae of the law and the way some people manipulate it to their personal gain, but in the end, it is the law which compels us to first act justly. I am all in favor of the discretion of judges to impose an overlay of compassion or outrage when there are extenuating circumstances. (For compassion, see Judge Frank Caprio. For outrage, nobody beats Judge Judith Sheindlin – don’t let the smile fool you.) But the more specific the statute is, the less opportunity there is for abuse. It can take awhile for the law to catch up with society, and this sorry case is a good example. Most of the exchange between the boy and the girl took place by text. In fact, they were in different cities during the last months of the boy’s decline into fatal depression. Anyone who has jumped to an emotional conclusion after receiving an email that cannot convey a disarming smile, a sarcastic intonation or a stricken look understands that what the reader imposes is rarely what the writer intended. Difficult debates are necessary, not just about public social media, but private electronic communications as well if we are to prevent uncertain circumstances like this from becoming more common. Jewish law is often denigrated, even by Jews, with the adjective “legalistic,” suggesting that what is served by debate over a point of law is the legal system itself, not the people who must abide by that system. Certainly, there are plenty of examples that look to validate that criticism. I love to study the section of the Mishnah (the compendium of case law based on the application of the Torah) at the very beginning of the section about Shabbat. It discusses carrying between a private and a public domain (think house and street), which is prohibited. But in this detailed articulation, further expanded in Talmudic discussion and commentary, is instruction about how a compassionate householder can feed an itinerant homeless person without either of them running afoul of the restrictions on portage and commerce. One can strictly observe the law – that is, serve the system – and at the same time show compassion to someone in need – that is, serve the person. Some scholars believe that the original Torah was just four books long. The fifth Book of Moses, Deuteronomy, is a rich source of legal and moral guidance, all placed in the mouth of Moses as his valedictory. But the action ends with the verse above. Maybe the original anthology was meant to convey the very specific limitations of “revealed knowledge” by concluding with verse that heads this column with who, what, when and where (and “why” presumed). But almost immediately, it was pretty clear that there was no such thing as comprehensive law that cannot be challenged by unanticipated circumstances. So – the Fifth Book. And the Talmud. And the codes of Jewish law. And modern and contemporary study and application. In my professional life, I live with my frustration with those who manipulate the good intentions of laws designed to protect religious minorities from discrimination by dominant religious practice. The crass reinterpretation of statutes designed to protect head coverings and daily prayer breaks has led to the awful consequences that afflict certain people seeking marriage licenses or indicated health care from people with “religious objections.” As an advocate, I am exasperated. As a private Jew, I am intrigued by the debates ahead in the halls of Congress, in state capitals and in every court in the land. We aren’t yet near Deuteronomy on this one! ----------------- This is the last column in the Numbers:13 Project, being inspired by the last verse of the last chapter of the book. After a hiatus of some weeks, the final series in this years-long project will commence. Watch for The Last of Deuteronomy, beginning sometime after the secular new year and concluding with fall Jewish holidays.

0 Comments

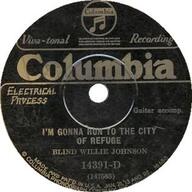

REFUGEES The Numbers:13 Project The towns that you thus assign shall be six cities of refuge in all. Numbers 35:13 In these columns, I usually start with something contemporary and find some resonance in the Biblical verse. Ordinarily, I do not interpret and apply the verse as I might in a brief lesson in a synagogue or other religious setting. But I will offer here the exception that proves the rule. This small verse comes near the end of a long legal instruction about manslaughter – the crime that occurs when one person takes the life of another with neither malice aforethought nor intention. One classic example given in the Bible is when two friends go off to chop wood and, as one is swinging the axe, the head flies off and strikes the other dead. The next-of-kin of the victim has the legal right to take the life of the perpetrator. In order to avoid more bloodshed, the manslayer may flee to one of six designated cities of refuge where their life is protected. The avenging kin is prohibited from harming his prey as long as the person he is chasing remains in the city. The Biblical Hebrew term for such a city is the same word as “shelter” in modern Hebrew. It is painted on every bomb shelter in Israel, which means you can’t walk five minutes in any populated area without seeing it. The word carries with it the notion that a person seeking such shelter is trying to avoid bodily harm, perhaps specifically death. But lost in the way we understand the term today is the very important detail in the Biblical story that the pursuing kin has the right to take the life of the pursued perp. That is, the right, but not the obligation. If the boiling blood of the bereaved has cooled, they may choose not to seek the death of the otherwise innocent person. But even if a promise – even if a vow – was exacted from the next-of-kin, should blood boil again, the original risk to the offender remains. That person is and remains a refugee; that person is and remains entitled to refuge. (There is an end point to this standoff. With the death of the High Priest, mostly a generational event, the slate is wiped clean, presumably because such an occurrence provokes an internal reset for the entire population. Otherwise, the ability to remain a refugee is permanent. And others may decide to live in the city of refuge, even without the need for protection.) Now, let’s come back to contemporary matters. The politics of how we describe migrant populations are complex. People uproot themselves for all sorts of reasons, but it is rarely out of a simple desire to leave home. Poverty, lack of resources, repression, oppression, ambition, even greed may play into a decision to quit a native land. I myself know many people from multiple generations whose accomplished parents – doctors, professors, engineers, thought-leaders – have given up a life of recognition and security to come to the United States and work in reduced circumstances so that their children could lead a better life. I knew couples who scooped up their young children and moved to remote places after September 11, 2001 out of fear for war against the United States. And I know young people who came to this country to make money, sometimes to bring their families and sometimes to live luxuriously (and sometimes both). But when someone shows up fearing for their safety, by whatever term we describe them, that person is a refugee. That person needs shelter from a danger that pursues them. In another town, in another time, I knew an unlikely refugee. She showed up with a young daughter, and she had a haunted and hunted look. Sure enough, she was fleeing from an abusive husband who had threatened to take away the little girl and punish -- maybe kill -- his wife. She adopted an assumed name, cut off communication with friends and family and sought shelter. The details of the story made it sound too lurid to be believable by my young self, not yet a witness to the deplorable things human beings can inflict on each other, But the community took in this small and frightened family. One day, the woman came to my office to tell me her husband had dropped dead, literally. He was driving somewhere, felt distress, parked his car, rang a stranger’s doorbell and collapsed on the front step. Gone. And he took with him the fear and despair of his wife. She and her daughter reclaimed their identities and went on to live their lives. They were able to do so because strangers offered them refuge without demanding evidence or proof. Had we declined, they might have been lost, or worse. Long after the fact, I have realized it didn’t matter if her story was true. She didn’t need to be a true refugee to live in a city of refuge. The practical function of the city of refuge is to save innocent lives. But the very existence of such a city is an expression of the values of the society that provides it. Woe to those who turn away people claiming to be fleeing for their lives. They may eventually wash the blood from their hands. But even if there is no blood to wash, they will never warm their stone-cold hearts. (Looking for something more uplifting? Visit www.thesixtyfund.weebly.com or click on the link to The Sixty Fund above. Two new awards were made in November 2019.) |

Archives

October 2023

Categories |