weekly column

|

Each week, find a commentary on something connected to verses of Torah or another source of wisdom

|

|

Each week, find a commentary on something connected to verses of Torah or another source of wisdom

|

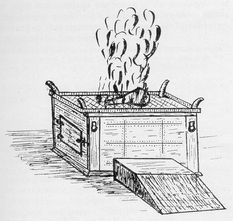

The Exodus:5 Project Then take the vestments, and clothe Aaron with the tunic, the robe of the ephod, the ephod, and the breastpiece, and gird him with the decorated band of the ephod. Exodus 29:5 The college graduation season swings into high gear this month and does not wind down until the middle of June. Tens of thousands of graduates, most of them at the beginning of their adult lives, will have degrees bestowed upon them as they parade in identical robes and silly hats. The initials of those degrees will land on their resumes as permanently as a tattoo. With good luck, they will not also come to regret the degree. Not all the graduates will be guided in their work life by the degree they earn. Even some of those with graduate degrees, including people with professional degrees like doctors and lawyers, will choose a different path early on. But many will start down a road highlighted on the map of their lives by the education, inspiration and validation they received in undergraduate and/or graduate school. It is not all the baggage they will take on that journey. Friends, music, books, politics, sports, student loans and other things will follow them during the first years – maybe more. Some will be lost, others will take their place. But almost everyone will believe that the person under the gowns they wore at graduation is essentially the same person who, forty or fifty years later, is ready to give up the work of their adult life and return to the person who set off down the road. It is not true. When I read the description of the first robing of Aaron, I cannot help but think of the sunset of his life, when he is stripped of these very garments. While the pageantry of this dry description is often read with disinterest, the meticulous dressing of the High Priest for the first time as he is officially invested with the authority of his life’s work ahead is filled with foreboding to those who know the end of his story. Day in and day out he will be responsible for the rituals on which the Israelites depend. He will preside over collective transgression, lose half of his children on the most important day of his life and contend with rebellion from within his own kinsmen -- experiences for which his holy instructions did not prepare him. But they all left impressions, to be sure, that penetrated beneath the tunic, the robe, the ephod and the breastpiece. So connected with his priestly responsibilities had Aaron become that, when it came time for him to die, Moses took him to the top of a mountain and removed the clothing that symbolized his work. Moses dressed one of Aaron’s surviving sons in those same gowns. And Aaron died. It is a lot of years since I put on a graduation gown to be called “rabbi” for the first official time. Nothing remains in my wardrobe from that day – the gown was rented, and the suit seems to have shrunk about four sizes. The baggage I took on my journey has changed, but never disappeared. I like to think that underneath my prayer shawl, I remained the same person. It is not true. I talk with a lot of my contemporaries who are asking themselves what their next chapter will be. Having spent so many years in one kind of work – primarily, but not exclusively, the pulpit rabbinate -- they wonder what else they can possibly do. They can do a lot of things, is the correct answer, but they may not yet have discovered the ones they want to do. The more poignant question is what has penetrated the tunic, the robe, the ephod and the breastpiece that they think they have removed. I do not mean what lasting impression the significant moments they experienced have left. Of course we are changed, all of us, by deathbed visits, students whose excellence we have provoked, guidance we have invented for the lost who sought our direction and so much more. I mean what impact on that self-beneath-the-robe has been created by years of leading and not following, of having the authoritative answer, of controlling others’ behavior by telling them to stand or sit or bend their knees. The inside person, so motivated by the spirit of learning and discovery before the authorization of the office, may look forward to returning the robes and taking a seat in the crowd. Inevitably, it isn’t so easy. I had a profound conversation with a friend and colleague who has had my experience of leaving the pulpit. He said to me that our Judaism had been deeply altered by the constant demand that we perform it for others. He has found it impossible to take a seat among every-day Jews and listen to someone else tell him to stand, sit or bend his knee. No one told us this would happen. And if they did, we never would have believed them. Maybe things are not quite so pronounced for the doctor or attorney. May the scientist doesn’t miss the lab, the teacher doesn’t miss the classroom, the social worker doesn’t miss the client, the writer doesn’t miss the assignment. But I have come to understand that whatever your sacred calling is, it saturates your outer layer and infuses what is beneath in incremental and imperceptible ways. Graduates won’t hear it. But when they finally take off the ephod, they will know Aaron not only at the dawn of his mission, but also at the sunset.

0 Comments

The Exodus:5 Project They shall receive the gold, the blue, purple, and crimson yarns, and the fine linen. Exodus 28:5 In a compact laboratory in a close-in suburb of Tel Aviv, Dr. Zvi Koren has unlocked the mysteries of snail juice. He has identified the science behind Biblical dyes that produced purple and blue colors. Certain snails at certain points in their development with certain exposure to the sun and elements produced the range of colors identified as blue and purple, used ritually to adorn the priests and color the fringes of everyday prayer shawls. If you visit the Shenkar Institute, Dr. Koren will show you his work (and other things as well). You will understand that the rarity of the colors results from the special skill it takes to know how to produce them. Today these colors are mostly intellectually interesting. Some observant Jews have used them (and other hues identified as the colors) for prayer shawl fringes, but mostly they exist to illustrate the past. We have no more officiant priests who need to be robed in the vestments of their office. But that doesn’t mean that colored garments are insignificant in our time. Most obviously, clothing of particular colors identifies the wearer as a member of a team. Sports teams choose a dominant color scheme to identify themselves on the playing field (and to sell merchandise to fans). Teams of military personnel distinguish among their services by the dress and combat uniforms they wear – green, blue, white and otherwise. Gangs – teams of a very different kind – choose particular colors of bandanas, sneakers or hats to declare their authority on the streets. (The classic movie “The Warriors” is especially invested in such attire.) Colors have other meanings as well. We have assigned meaning to traffic signs and signals – red light stop and green light go (don’t forget that yellow light means slow). Green has acquired an association with environmental responsibility. When you are feeling blue (or singing the blues), there is an ache in your heart. Beige is considered neutral in all sorts of positive and negative ways. But no two associations with color are more controversial these days than pink and blue. Once universally assumed to distinguish between girls and boys, lots of parents, including some in my own family, have stepped away from the stereotypes that baby clothes and motifs represent and reinforce. I have no idea if there is a science to such associations with color. My perfect three-year-old granddaughter, raised in an environment of shared parental responsibilities, gender-neutral baby toys and various pastels and primaries across the palette, has a distinct preference for pink and all the frills and froofiness you can think of. She will clamber up a jungle gym and leap off the third step up, but the colors she chooses are shades of pink. Is there a language to colors that speaks to us in mysterious ways? Gold, blue, purple and crimson yarns are considered rich and royal. Did we imbue those colors with their meaning, or do the shade and depth of colors convey something inherent? Certainly, the priests who were draped in the finest linen dyed with the rarest or most desired hues were identifiable by their garments – not so much what we today would call fashion, but by the adornment with tints that conveyed a message of holiness and chosenness. Someone reading this column will know if there has ever been a study of what the choice of a favorite color means. Perhaps there has also been a comparison of dominant colors among different cultures. And we have certainly come to understand in real and symbolic ways that the rainbow that contains every shade of visible color puts no greater importance on the reds or the blues; in fact, the spectrum is incomplete without every imaginable shade. Dr. Koren may have discovered how our ancestors manipulated dyes to create the colors they wanted. In that regard, he is a person of color. But in the end, aren’t we all?  The Exodus:5 Project Set the mesh below, under the ledge of the altar, so that it extends to the middle of the altar. Exodus 27:5 I hope that you recognize the premise of the joke that is contained in the title. If not, I will spoil it for you. A nudnik (look it up) in the synagogue keeps imploring the rabbi, “Make me a levi.” After many conversations about why that’s not possible and a large contribution that is persuasive, the rabbi declares that the nudnik is a levi. Asked why it was so important, the nudnik says, “It is a matter of family pride. See, my father was a levi, my grandfather was a levi, my great-grandfather…” A levi, or as he is gentiley known, a Levite, is descended from the tribe of Levi, designated by the Bible to serve the ritual needs of the other tribes of Israel. A single family from among Levi – descended from Aaron – are the priests. The Hebrew word for priest is kohen, but for whatever reason, the joke is funnier with “make me a levi” than with “make me a kohen.” Status as a levi or a kohen is mostly family tradition, though if your last name is Levi, Levy, Levine, Levin or Loewy or Cohen, Cowen, Kahn, Katz or Ginsberg (don’t ask), you just might be Levitical. I am of the opinion that there is a little levi in every man. I say that because of the magnetic attraction we all seem to have to backyard barbecue grills. Whether the disposable ones you pick up at Walmart, the classic Weber, the gas-fired KitchenAid Land Rover or the Big Green Egg, men like to poke at meat on the grill with a stick. (Vegetarians do not poke at meat but are still drawn to squash and artichokes over charcoal.) I do not know whether the ancient sacrifices provoked the fascination with a seared steak or if the Passover lamb roast just sort of caught on, but the smell of smoke seems to have evoked a sense of comfort among those who were concerned with being in the good graces of God. Even in traditions that have no legacy of sacrifices, it is not unusual to find incense used to enhance and enable peace of mind. You might call it mass aromatherapy. It is probably considered sacrilege by some that I would refer to the altar in the Tabernacle as a giant pit barbecue, but that is what it was. Hard to visualize from the very specific and very arcane instructions, the “mesh” in the verse above is really a grill, shaped to sit half-way down the structure and hold the sacrifice over the fire. Some pieces of the animal were burned up, but the meat was part of what sustained the priests after it was cooked. The burnt offerings fed not only the spiritual life of the Israelites, but also those who tended to spiritual needs. King Solomon famously observed that nothing was new under the sun, so I am relatively certain that the origins of roasted meat are not in the Biblical sacrifices or even among the early Hebrews. For reasons I cannot explain, even in the most patriarchal of societies, men seem to gravitate to outdoor cooking. It may be the urgings of ancient hunter-gatherer DNA or the residual memories of ancient temples, but transporting the receptacle, building the fire and grilling the meat still holds some sacred resonance for so many men. There is a lighthearted tone to this little bit of writing, I know. However, my message is serious. Primal inclinations, though transformed and even sanctified have survived to contemporary times. A stack of firewood, a pile of briquets, or the (decidedly inferior) flaming propane can still draw the spark of a levi out of the most modern of men. Contending with fire, making it serve our purposes from corn on the cob to burgers to marshmallows ignites some mystical impulse. The results are most satisfying, both s a meal and from the appreciation of those who partake in the feast. If the weather ever warms up in the spring of 2018, a less and less likely possibility, the grills will fire up again. Be it vegetables, fish, poultry or meat, men will walk out the back door and into the past to prepare a meal over the fire. When I take a minute to reflect on what I am doing, it will not necessarily make me a chef. But for a moment, it might make me a levi.  The Exodus:5 Project Make fifty loops on the one cloth, and fifty loops on the edge of the end cloth of the other set, the loops to be opposite one another. Exodus 26:5 The institutionalization of religious skepticism in this country may very well be traced to a line of dialogue in the movie “The Wizard of Oz.” (Spoiler alert) When the little dog Toto pulls back the cloth that conceals the wizard, revealing him to be nothing more than an illusionist, he attempts to gain his status back by making his projected giant head say, “Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain!” Like most of you, I have deployed that line in many circumstances. More than twenty years ago, when the synagogue I served was under renovation, we conducted High Holy Day services in a local church. They were completely accommodating when we asked if we could construct a screen that would conceal the stained-glass representation of Jesus that presided over the front of the sanctuary. When I arrived on the morning of Rosh HaShanah, I realized that the church’s architect had taken advantage of the sun’s position on Sunday mornings to illuminate the giant glass mural. Projected onto the screen, even more ethereal than in the glass, was the human likeness. Never have I had a better opportunity to say, “Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain.” I don’t know if Noel Langley, who wrote the script, knew he was giving voice to the doubt that plagued so many. While the sentiment was not new – after all, the same premise is the point of “The Emperor’s New Clothes” – the notion that ruling authority relies on illusion and concealment rather than honesty and transparency mostly applied to political cynics. It still does. But the Wizard of Oz himself was part emperor, part priest and part god. If ever, oh ever, a wiz there was, the Wizard of Oz is one because…well, because of his cultivated reputation. In the movie, he is exposed to be a carnival performer. (In the book, he has a bit more prestige.) And once the curtain has been pulled back, his four petitioners call him what he admits he is: a humbug. As a piece of entertainment, it is a great denouement. But over the few generations that the movie has impressed itself on generations, it also planted the seed about pulling back other curtains that conceal those who would call themselves wizards or emperors or priests or even gods. It adds to the irony that in ancient times, before streaming or even VHS tape, “The Wizard of Oz” was broadcast every year at Easter and Passover, the time of miracles, quests and looking for home. And I also note that one of my children who liked playing rabbi at three years old decided at age five that when she grew up, she wanted to be Dorothy. These days, every curtain begs to be opened. Whether the manipulations behind are thus revealed or we discover that there really is nothing back there, we demystify every tantalizing spiritual mystery we encounter. Those of us who have been disabused of our grandparents’ faith have more than a tendency to look askance at the segment of our population that prefers to keep the curtains closed, attributing to them a sort of willful ignorance. We presume that if they want the curtains closed, they also want the closets closed, the gates of heaven closed to people unlike themselves and, ultimately, their minds closed. It may be true of some, but no less true of some skeptics. Perhaps they do not want to know first-hand what Noel Langley introduced to the movie-going public: there is nothing behind the curtain that isn’t already on the other side. After all, the Scarecrow, Tin Man and Lion all get what they came to get. The diploma, the clock and the medal are no more repositories of wisdom, compassion and courage than the wizard’s projector bestows authority. Everything everyone needed was at hand, waiting to be recognized. The little fragment of instruction that makes up this verse is about the curtains that surrounded the Tabernacle. When the portable sanctuary was erected on otherwise unremarkable ground, it created a visual reminder of the intersection of the fantastic and the everyday, the sacred and the secular. The land was neutral. The curtains (and everything else) were made by human hands. But in constructing this designated precinct, the Israelites were hoping not to conceal, rather to reveal. God had promised that if they built it, then the divine presence would abide. As so many of my teachers have noted, the promise was not to abide in it (i.e., the Tabernacle), but to abide in them (i.e., the Israelites themselves). The man behind the curtain discovered that his real power was within, just as surely as wisdom, love and courage. And as for Dorothy, she pulled back the curtain of dreams to live a full and grateful life in the place she called home. More and more Americans are religious skeptics, and we may be able to trace that to “The Wizard of Oz.” But we don’t really need smoke and mirrors to discover the gifts that empower us and give our lives meaning. The curtains were made by us reveal our potential, not to conceal a wizard.  The Exodus:5 Project tanned ram skins, dolphin skins, and acacia wood Exodus 25:5 I have some friends on Facebook who are always posting pictures of things that don’t exist anymore except as historical artifacts and quizzes about terms that “kids these days” do not understand. When email first became popular (yeah, in my adult lifetime), it began with lists of what you wouldn’t know about if you were born after a certain year. Then there was a great sight gag in the John Travolta movie “Michael” in which a young model is stuck in a rural motel and wants to call a cab to get her out of there. The desk phone had a rotary dial, which she keeps poking trying to connect, all to no avail. Ha ha. These days Tom Hanks sells a book he wrote entirely on a typewriter. The round receptacles in your car for your phone charger were designed to heat cigarette lighters. Vinyl records are heralded for the very imperfections that made them give way to compact discs, which are now just CDs. At some point, lights, faucets and toilets will operate everywhere with the wave of a hand, only to be replaced by the embedded chip in your body. (I already have a device on my keychain that opens anything with a personal password.) Words that we use today have original meanings that are lost to contemporary usage. A port for a USB or HDMI cable has the same function as a port for airplanes, which borrowed “airport” from “seaport.” There is no presumed humor in comic books, which have expanded to become graphic novels, which used to be sold from behind the counter in adult book stores. And the phrase “never again,” these days preceded by the hash tag, is yet another phrase borrowed from reactions to the Holocaust that are trying to recapture their original meanings (like, for example, the word “holocaust”). The globalization of language has created a similar dilemma. When I took French in junior high, we learned about “Le Weekend” and the outrage it provoked in the purists who demanded “le fin-de-semaine.” Early architects of modern Hebrew translated “telephone” from the original Latin and named the device “sach-rachok.” Of course, it is called “telephone” throughout Israel. And when I was asked to choose what my granddaughter would call me, I thought I would be clever and suggest “sababa,” Israeli slang for “cool,” and one syllable added to “saba,” meaning grandfather. Well, that was one syllable too many for a little girl and now I am “Baba,” making me a father in Persia, a grandmother in Poland and pureed eggplant in Whole Foods. (BTW – I wouldn’t change it for the world.) When people read the Bible in English, as most Americans do, they are at the mercy of translators. The Church of England scholars who provided King James with his authorized translation chose the word “horns” instead of “rays” for the description of Moses’ beaming face, creating a fiction about Jews that persists to this day in some parts of the world. The distinction between “you shall not murder” and "you shall not kill” is of enormous significance. And entire religious perspectives have depended on the difference between “young woman” and “virgin” in various translations. In fact, the Italians have an idiom, “tradutorre, traditore,” hard to capture in English but meaning “translator is traitor.” Therefore, reading the Bible is sometimes very difficult for people not familiar with the ancient Hebrew in which so much of it is written. That observation can lead to a certain patronizing smugness, I know, but it does come in handy when people who read and interpret English very closely try to tell me what they understand from a twentieth-century English translation of a Greek text reporting an Aramaic speaker interpreting a Hebrew phrase. That’s not to say that reading the Bible (and other texts) not in the original is futile, but if literalness is a fatal flaw in the original (and it is) then it is disabling in translation. And the reason that is such a serious problem is that faith must be grounded in truth or it is faith in what is simply not true. So, when I am asked about where the fleeing slaves who left in such a hurry that their bread couldn’t rise managed to find time to collect not just tanned ram skins and loads of acacia lumber, but dolphin skins, I know that it’s a skeptic’s question about more than the presence of aquatic mammals in the wilderness. (And no, they were not snatched from the walls of water as the Israelites crossed the sea…) There is an answer to this question (that is, the one about dolphin skins) and it is this: nobody knows what the original word means. A thousand years ago, one commentator claimed it was an animal by then extinct that had multi-color skin. Another commentator claimed it is a giraffe (also abundant in the wilderness). Many before and since have sought to explain the meaning of the Hebrew word – including a modern commentator who believes it is a beaded cloth – and all are without corroborating evidence. That may be why that first list of things kids who were born after I came of age don’t know includes dolphin skins. On the one hand, language is enormously important. It is the primary way that information, knowledge and wisdom are conveyed not just between two contemporaries but from past generations to future ones. On the other hand, no word – not even the new ones – comes with a pure meaning. We layer our language with meaning, rearranging the new and the older and the ancient to suit our purposes. Or our porpoises. Excuse me: our dolphins. |

Archives

October 2023

Categories |