weekly column

|

Each week, find a commentary on something connected to verses of Torah or another source of wisdom

|

|

Each week, find a commentary on something connected to verses of Torah or another source of wisdom

|

0 Comments

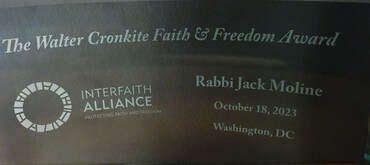

I was deeply honored to be presented with the Walter Cronkite Faith and Freedom Award by Interfaith Alliance, where I am president emeritus. These are the remarks I offered on October 18, 2023. They are pretty good. It may be a little pent-up energy from not having to write High Holy Day sermons any more! I have spoken at many of the Walter Cronkite Faith and Freedom Award events, and my typical role was to be the person to ask for money. In fact, I saw all sorts of hands clasp wallets and pocketbooks when I reached the podium. Relax. I am not that guy tonight. But he’s coming. This award was one of Welton Gaddy’s big ideas. It started as a project that convened a blue-ribbon panel to find a recipient for the Faith and Freedom Award – the first designee was former president Gerald Ford – and it devolved into what you see tonight. Me. But in between, came Walter Cronkite, who had retired from his years anchoring the CBS Evening News after a stellar career as a journalist, primarily in broadcasting. It is cliché already, but he was known as the most trusted man in America, and when he retired, he trusted Interfaith Alliance. I was on the board already when it happened, and I can tell you that but for a small glitch a few years earlier, this award might have been called the Bruce Hornsby Faith and Freedom Award, which would have set a different direction for us. But it is the direction we took that is the subject of my musing tonight. The vision of the earliest days that inspired Welton and attracted Walter also inspired a young pulpit rabbi named Jack Moline. Me again. The notion was pretty simple: an unholy alliance between cynical political conservatives and radically right-wing evangelical Protestants conspired to upend some of the bedrock principles of American society. For the conservatives, the goal was smaller government and freer enterprise. For evangelicals, it was the preservation of what they perceived as the hegemony of White evangelical Protestants who, out of sufferance, tolerated other Christians, Roman Catholics and Jews, but considered those who would not affirm the dominion of the King James Bible to be citizens of a lesser status. It seemed almost like a cartoon squabble, played out on cable television and a program that most people never watched – the Old-Time Gospel Hour. A slightly – slightly – less unholy alliance between Democratic Party operatives and liberal clergy arose to do combat. But the clergy – Protestant, Catholic and Jewish, and shortly thereafter Muslim, Sikh and Buddhist – were having none of the direction that the Democratic operatives were offering. They doubled down on the Constitution and declared, as a matter of faith, that, as we say in Aramaic, dina d’malkhuta dina, which, as you know, means “the law of the land is the law.” And that very principled stand is what energized Welton Gaddy. And any time he was persuaded to veer off that message, he’d get a phone call from Mr. Cronkite who, with clear eyed-insistence, reminded Welton that the challenge to America, the one he signed on to endorse, was from religious extremism and not the issue-du-jour. We were then – as we were during my tenure – the only national organization doing that critical work. It is to remind us of that mission that this award is called the Walter Cronkite Faith and Freedom Award. It has been well over 40 years since Mr. Cronkite gave up the anchor chair at CBS, which means that people who became habituated to watching the evening news are the target audience for Rybelsus, Prevagen and Joe Namath’s Medicare Coverage Helpline – call now, it’s free! Me again. Designating me as a recipient of this award is a recognition that I did my best to uphold the unique approach of Interfaith Alliance. I talked about it just a little yesterday when I paid my small tribute to Welton. It is more than a matter of claiming that injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. That’s an important and endorsable crie-de-coeur, but it is not enough. Interfaith Alliance takes the next step – I had the sad privilege to articulate it three days after the 2016 elections when the president-elect announced his intentions to register Muslims. If that happened, I said, then register me. I am a Muslim. And that’s the legacy I inherited from Welton. If I am denied the right to vote because I am Black or poor or speak a different primary language, then I am Black or poor or speak a different primary language. If I cannot marry because I am gay, then I am gay. And if I am prohibited to hold public office because I proclaim Jesus Christ to be my Lord and Savior, then I – even I – proclaim Jesus Christ to be my Lord and Savior. Radical empathy is what our Constitution demands and what my faith teaches. It is what was cultivated in my heart by my service to this organization and by my friend Welton. All the other stuff challenging our country, our democracy, our citizens are the results, not the cause of our losing sight of the value of every human soul and of every person’s rights. Returning Toni Morrison or Anne Frank to a library is a victory in a skirmish. Unlocking the doors to a reproductive clinic is a correction of an act of bullying. Making artisanal baked goods available for a lesbian wedding is the repudiation of a person’s prejudice. Interfaith Alliance is by principle obligated to support the people who oppose those injustices. But the cause of the effect, the belief on the part of a large minority with outsized influence that their convictions must be affirmed by our society even at the cost of the human rights articulated in the only sacred document that governs the United States – the Constitution – the cause of that effect demands not only a tactical approach, not only an issue approach, not only a coalition-of-the-willing approach. The cause of the effect cannot be addressed by using whatever name is attached to distract from the root – Christian Coalition, Moral Majority, Values Voters, Tea Party, White Pride, Christian Nationalism – in promoting our agenda of equal rights and protections. It must be addressed by words and deeds that emerge from the heart and enter the heart. That is our unique contribution to this critical struggle to protect our first freedom. Empathy, radical empathy, can be very hard, especially when we have limited sympathy for some of our community. What Interfaith Alliance asks of you is to hold precious the people you cross the street to avoid, who attend the houses of worship you will not, who eat the foods you abhor, who speak the languages you do not understand, who affirm the sacred texts to which you object, who look askance at you for the very same reasons. Without teaching and modeling that the great blessing of America is less about celebrating and protecting what we presumably have in common than celebrating and protecting what makes us so different from one another, this nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated will not long endure. The former is what is so skillfully and deviously foisted on a frightened and insecure segment of America by our opponents. The latter is the mission I inherited and had the privilege to represent. I learned a tremendous amount from my years at the helm of Interfaith Alliance. I learned it primarily through the people whose work in the weeds gave them deeper insight than mine in the manicured fields. Jay Keller, Isa Hyde, Ari Geller and the team at West End Strategy, were all in place when I arrived and when I left, except for Jay who snuck into retirement ahead of me. I cannot say enough about Ray Kirstein and his extraordinary eye for the very people for whom we exist – the ones whose faith commitments and perspectives too often escape the notice of those of us so principled about protecting them. The members of the boards that gently oversaw our efforts, led by Fred Garcia and Jay Worenklein, and supported so generously by so many others, most intensely by Julie Baugh and her family’s Baugh Foundation. I know I am in trouble trying to name some names here, but there are two people with whom I go all the way back to my early days at what was then TIA. Claudia Wiegand got roped into the board out of devoted friendship that began in my wife’s book club, and she was actually the very first person to suggest I succeed Welton. And David Currie who was at the time the only person I ever knew in all of West Texas has proved over and over again that if they can grow ‘em like him out there, there is no explaining the rest of the state. I want to mention also Katy Joseph, who did so much to shape our maturing into areas of concern on the ground that would have escaped my notice at the altitude I preferred. There’s a Talmudic teaching, make someone your teacher and acquire a friend. That’s Katy. As for the rest of you, please forgive me for overlooking your name or the names of the people unable to be here tonight. Or don’t. I’m retired. I had a little trouble figuring out how to end these remarks. I was preparing them in the midst of a family tragedy that pulled at my heart and my focus with relentless cruelty. But I got a small respite about ten days ago when an essay appeared in the Washington Post written by columnist Kate Cohen who has written a book publicly declaring herself an atheist. God bless her. In my days at Interfaith Alliance, her right to be unfettered by the arrogance of religious practitioners was just as much our concern as anyone professing a faith. However, most of the essay was her critique – no, let me call it her denigration – of the entire endeavor of religious devotion. You have heard it all before, though not always as eloquently. Religion is too privileged and not responsible enough. It is arrogant even in professing its compassion. It is invested in a fantasy and disconnected from reality. It is the source of oppression, bigotry, divisiveness, abuse, hatred, and repressiveness. She’s a good researcher and a good writer, though I hasten to add she is an opinion writer, not a successor to Walter Cronkite. But, to quote my late friend Welton, I’ll tell you what. She’s not wrong. I am not sure she is right, but she’s not wrong. You and I, we are going to go back to our synagogue, church, temple, gurdwara, mosque, meeting hall, or other sacred precinct and run the risk of being lulled into complacency over how we have allowed so many Americans and so many others to see what we do in our faith communities as sowing a sense of division with those unlike ourselves. But it is not enough for those of us who are here tonight, who support Interfaith Alliance, to combat the hatred among our faith communities and within our faith communities for people who diverge from the teachings of our faith communities. Radical empathy is not only for the public square. It is for your sanctuary. It is for your scripture study. It is for your family table. It applies to your uncle the MAGA Republican and to your aunt the socialist, to that kid from another religion or no religion that your cousin is dating – not to affirm that they are right, but to affirm their rights. For us, supporting beliefs and convictions and faiths must be an inviolable matter of the Constitution, and supporting the Constitution must be an inviolable matter of faith. That’s the only way Interfaith Alliance can work. That’s the only way our country can work. I sound pretty passionate and maybe a little wise. But I am 71 years old and retired, and it took me more than a little while to get here. I remember Welton telling me when a TV anchor who was not Walter Cronkite was given this award for his coverage of a national emergency, even though he was notoriously hostile to Jews, that the Faith and Freedom Award was not for lifetime achievement, but for a singular achievement. My qualification for this award is for the singular achievement of being saturated to my soul by the good work of the organization that chooses to honor me tonight. I hope I have advanced the cause so that it does not take so many years to change the hearts and minds of another generation. For that singular achievement, I rely on you. And so does this beloved country. Thank you all for this great honor. PS -- Weekly columns are returning very soon. My first trip to Israel was the summer after I graduated from high school. I was eighteen. The eight weeks were transformative. Of course, I toured and saw the landmarks of history, ancient and modern. But there were experiences that could have happened only in Israel that made an impact on my soul. One was the morning our guide took us to the top of Mt. Arbel in the Galilee to give us an overview of the land. When he finished, he clapped and said, “Okay, back to the bus.” We stood and turned around, at which point he shouted, “Where do you think you’re going?” And then he pointed at our buses parked at the bottom of a sheer cliff. We climbed down together, astonished at what we accomplished. Another was the week we spend excavating the archaeological dig at the south wall of the Temple Mount. I shlepped and sifted dirt from a small room, reaching deep into history, and recovering coins, dice, bones, and more. When I visit that now-completed dig, I can still identify the location of my very small contribution. And then there was the singing. We were visited just a couple of times by a young woman with a guitar. We learned “Shoshana, Shoshana, Shoshana,” “A Night Like This,” and a modern setting of the end of Psalm 128: May God bless you from Zion. May you see the goodness of Jerusalem all the days of your life. May you see your children’s children. Peace on Israel.” These and other songs became the soundtrack of my life, right alongside the music of the Beatles, Stevie Wonder, and Linda Ronstadt. I guess I could have been inspired by an encounter with nature anywhere in the world, and there is no shortage of opportunities to drill down (literally) into history wherever people have lived for many generations. And music triggers emotions that flourish in any setting. But these were my memories, and fifty-plus years later, I still live into them. Not too many years ago I got another chance to descend the Arbel cliffs. And I have participated in other digs. And Psalm 128 makes a regular appearance in both prayer and study. But. This summer, I was awash in the blessing that the psalm promises. In 1970 and since, I was blessed to see the goodness of Jerusalem, which has stayed with me all the days of my life. In those intervening years, my wife and I had the privilege and joy of raising three extraordinary children; just this season, in the course of six weeks, all three of them were blessed with children of their own. I have seen our children’s children. I am so full of gratitude that there is barely room for air. Of course, there is one not-so-small piece of the blessing left: peace on Israel. It is the dream of generations, and not just modern ones. Is it overreaching to hope that the abundance that is mine, cherished and amassed over a lifetime, is one my children and children’s children will inherit? Not if we work for it. Not if we keep singing. My description of an ancient ritual and our family tradition comes as a prelude to an announcement of little consequence to anyone but me, but you deserve to know. The picture that accompanies this column represents our take on the mitzvah (commandment) to initiate Shabbat by lighting candles, with the appropriate blessing, at least 18 minutes before sunset on Friday. In Jewish homes, the moment is most often conducted by a woman, with others gathered around. The strictures of Shabbat forbid the kindling of a flame, but the ritual of reciting a blessing requires it to precede the action it sanctifies. Once the blessing to light candles is recited, it is Shabbat. And once it is Shabbat, you can’t light the candles. So, the woman lights the flame, waves her hands toward her face as if to gather the light, and then covers her eyes to recite the blessing. When she removes her hands, she beholds the flames as if for the first time, thus “kindling the lights of Shabbat,” as the blessing proclaims. But between the recitation of the statutory blessing and the beholding of the lights, time is frozen. In that pause, the woman has an intensely personal audience with God. Honestly, it does not matter whether she has a traditional belief in God (whatever that is) or is a committed skeptic, those intervening seconds contain a spiritual power that is second to none. Author Ira Steingroot correctly observes that “men davven (pray) together for hours in the synagogue hoping to achieve the drama and transforming magic of the wave of a woman’s hands.” During those seconds, the Holy of Holies opens to receive whatever she brings to offer: her hopes, her heartbreak, her anxiety, her anger, her longing, her love. My wife has occasionally volunteered what she offers in those moments, but I intuited from the beginning of our life together that it was not mine to ask. We are enough alike in our values that I have known since we first became parents that the well-being of our children in general and in specific was always part of the moment. I witnessed my mother light candles weekly for close to twenty years, and then whenever I was in her home for Shabbat for forty-some years more. She, too, took that time for something powerful enough to mist her eyes each week. It made an impression on everyone who experienced it. Near the end of her life, when she was bed-bound and unable to come down the half-flight of stairs to the candlesticks, her Filipina caregiver would light the candles, call her on Facetime in her bed, and hold the phone toward the candles so she could have that precious moment. It is traditional to light two candles to provide an extra measure of light for the joy of Shabbat, and they should burn for long enough to illuminate the evening meal and perhaps some singing and studying afterward – generally around three hours. We have inherited the tall silver candlesticks that traveled with my wife’s ancestors from Europe, and she began the custom of adding a candle for each of the members of our immediate family as it grew – five eventually. When our eldest found her soulmate, we added a sixth, and the addition of a candle on Friday night became the hallmark of welcoming new members to the family, including our two perfect grandchildren. You will notice in the picture ten candles – two in the silver holders and eight in the colorful set we acquired in Israel. (Yes, they are part of a Chanukkah set, but we have other holders for that!) And in front of those eight are three holders without candles. They were gifts for Mother’s Day this year, one from each of our kids. Over the course of June and July, God willing and medical science attending, each one of our three children’s families will give us cause to add a candle. Three first cousins, less than six weeks apart. Our hearts are so full we could burst. Those moments on Friday night between blessing and beholding are more intense than you might imagine. The announcement is an anti-climax. You now know why I am going to take a long break from these columns. All of my energy will be available to these little lights of mine. Maybe I will pop up occasionally in your inbox or news feed, but mostly I will be living in that moment between blessing and beholding.

|

Archives

October 2023

Categories |