weekly column

|

Each week, find a commentary on something connected to verses of Torah or another source of wisdom

|

|

Each week, find a commentary on something connected to verses of Torah or another source of wisdom

|

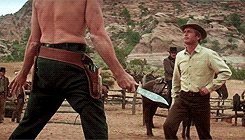

The Last of Deuteronomy Only trees that you know do not yield food may be destroyed; you may cut them down for constructing siegeworks against the city that is waging war on you, until it has been reduced. Deuteronomy 20:20 In our family, we tried to impose a rule at the dinner table. It was declared a QFZ – a “quote-free zone” – in an attempt to avoid the replay of scenes from movies like “Zoolander” from dominating the conversation. My wife and I had modest success, yet to this day our adult children, each with their own dinner table, deal with the intrusion of popular entertainment on the evening meal. At least I don’t have to hear from Strongbad anymore. If I am going to be honest, however, I have to own my personal transgressions. We once saw a play on Broadway that was a drawing-room farce called “The Norman Conquests.” (The main character was a guy named Norman.) In the cast was Ken “The White Knight” Howard, who had one line, spoken in response to everything directed at him: Ah. It is a staple of interaction between me and my wife. Likewise, the self-abnegating exclamation, “I blame-a myself,” spoken by Steve “Georg Festrunk” Martin on Saturday Night Live, pops up almost anytime that, well, I blame-a myself. When I see this instruction about laying siege to a city during wartime, it reminds me of another quotation that took up residence in my repertoire – though, thankfully, not in real-life circumstances. This permission to use trees for their wood follows a prohibition of cutting down trees that bear edible fruit. And that permission follows the requirement to call for peaceful surrender, even if belligerence between the two parties has transformed opponents into enemies. There is no fighting until the rules have been explained. Millennia later, Butch Cassidy is challenged by another outlaw for leadership of their gang. The presumptive replacement chooses knives for the confrontation. Butch refuses to begin until the rules are clear. “Rules in a knife fight?” says the other guy, as Butch approaches. Before anything else is said, Butch lands a boot between the other guy’s legs. As he collapses to his knees, Butch tells Sundance, “Say one-two-three go,” which Sundance does very quickly. Butch ends the fight with a two-handed uppercut. Rules in a knife fight? What a ridiculous concept. If the purpose is to win, then the only concern rightly ought to be who is left standing. Likewise, in besieging a city – that is, trapping the residents inside in the attempt to defeat them – what possible use could there be for rules? Any delay, any restriction might result in catastrophe for the combatants. And while it is the case that the nations of the world, in peaceful times, established conventions for the treatment of civilians and combatants in wartime, it is easy to see how they might be ignored by a military desperate to win. It takes someone of deeper conviction than the will to win to embrace and enforce the ethic of war. It takes someone who understands – as this verse insists – that looking beyond the moment of battle or even the end of hostilities is the wisest course of action. When a winner emerges, the survivors (numerous, we hope) will have to eat. Cutting down shade trees for battlements might be necessary but cutting down fruit trees puts the future at risk when the war is over. I have been watching (and resisting) a shift in the way our federal government has approached education over the past four years. Under previous administrations, public schools were the top priority of the Department of Education, a primacy that was mirrored on the state and, especially, local level. But the DOE has been led by someone philosophically opposed to the dominance of public institutions in educating the next generation of Americans. It is a little hard to suss out her exact reasons, but there seems to be an overwhelming dose of religious fervor in her campaign to fund so-called school choice. More than science or civics, she believes a proper education must reflect the values that a family (presumably) wishes to inculcate in the kids and, by extension, in society. All of our personal children spent much of their education in private schools with a Jewish foundation. We sought no public money to make that happen. We also paid our taxes gladly (no kidding) in support of the public school systems from kindergarten to university. Our choice of Jewish schools did not exempt our kids from curricular parity with the schools they might otherwise have attended. And the seats they did not fill when they were not in the public system were not ours to cash in – they provided fruits that sustained the siege against ignorance that is the constant battle of civic society and the educators who lead the charge, until ignorance has been reduced. Rules in a fight over full funding for public education? Say one-two-three-go.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

October 2023

Categories |