weekly column

|

Each week, find a commentary on something connected to verses of Torah or another source of wisdom

|

|

Each week, find a commentary on something connected to verses of Torah or another source of wisdom

|

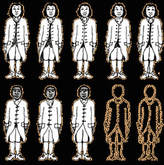

The Exodus:5 Project And Pharaoh continued, “The people of the land are already so numerous, and you would have them cease from their labors!” Exodus 5:5 I have been challenged lately in conversations about privilege in American society. Only people in deep denial would challenge the advantage of being white in America; while it does not translate into consistent benefit for every individual, it is true that in comparable circumstances, being white almost always puts a person closer to the head of the line than being of color. Jews may or may not be considered white by all white people, but they are closer to the head of those lines than others who are others. The term of art in discussing these circumstances these days is “white supremacy.” The choice of that term strikes me as purposeful. For those people who are pushing back on inequity and inequality in this country, the presumption is that even white allies accept their privilege as a matter of fact. Perhaps they are willing to voluntarily surrender some aspects of it, but they are not willing to have it taken because they have earned it…somehow. Calling privilege “white supremacy” makes every white American sound like an ally of the white supremacists, the alt-right, the neo-Nazis. Famously, anti-Muslim organizations try to thread a needle by distinguishing between “Islamic” and “Islamist” in their rhetoric. Most of the “anti-Islamist” organizations have a hard time identifying trustworthy Muslims, especially if they practice their faith. As a white guy (or an almost-white guy), I hear the lack of distinction between “supremacy” and “supremacist” in the same way. We are at this point in race relations in this country because of what Rabbi Dovid Asher calls the stain on our democracy: slavery. Enshrined in the Constitution is the notion that people of color are less human than white people. It is irrelevant to argue that the definition had to do with the census or taxation or the economy. Its effect bypasses justification, and we are seeing it hundreds of years and tens of generations later. The content of character is irrelevant; the color of skin is disqualifying. Here’s an absurd comparison, but it makes my point. Remember the TV series “The Jeffersons?” One story arc involved the mixed-race couple with two children, one with darker skin and one with lighter skin. It was shocking to hear the siblings argue over their resentment of each other because of the accident of their pigmentation. But more than forty years later, the President of the United States, the child of a mixed-race marriage, raised by his white mother and her white parents, was hailed as our first black President because his skin favored his African father’s genes. We continue to think of each other in sweeping categories and, as a result, we continue to advantage and disadvantage each other in purposeful and accidental ways. Each member of our family is older or younger, accomplished or challenged, lovable or curmudgeonly, musical or tone-deaf, clever or dull, fun or boring – all the distinctions that intimacy allows us to see. The members of other families are categorical. They are rich. They are nice. They are upright. Or…they are just the opposite. And those categorical approaches translate to roles assigned by society. They are the ruling class. They are the workers. They are the slaves. They are criminally inclined. They are the great unwashed. They are supremacists. It is ugly from either side, and it reduces human beings from subjects to objects. That is Pharaoh’s point (this time) to Moses. Your people are our labor force, he claims. We rely on them because they are so numerous. They are “the people of the land,” dirt people, mud people, clay people. What are we supposed to do if they all go on a three-day holiday? And it has an effect on “the people of the land.” They are diminished, unsure and fearful long after Pharaoh’s army is decimated before their very eyes. Who would blame them for turning this behavior back on the Egyptians? Yet they are instructed otherwise, specifically (in Deuteronomy 23:7) and generally throughout the Bible (do not oppress the stranger because you were the stranger in Egypt). I think about these questions from a position of advantage, to be sure. When I am confronted by my privilege or my supremacy, I must push hard against the sense of insult and grievance that interferes with my ability to hear the pain behind those descriptions. Whether I am fully guilty, or guilty of only three-fifths, I can draw an understanding of the humanity of others and how they have suffered by being diminished, unsure and fearful long after Pharaoh was deposed.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

October 2023

Categories |